Trust Your Instruments

There are a handful of things that stick with you when you’ve been trained as a pilot. They’re life lessons that have specific applicability to flying. They’re necessary to be fully understood if you want to be safe. One of the most important is trust your instruments.

Trusting Intuition

Most people have spent their lives listening to their thoughts and bodies and have therefore developed a “sense” about right and wrong. We’ve got all sorts of systems in our body that can measure orientation and which way is up, and for the most part, they work well. In the same way that you learn to ride a bike by feel, you learn to fly a plane by feel.

Everything is fine until you’ve got a bit of an ear infection and your vestibular system misleads you. It’s the system designed to measure orientation, and it’s often why people feel dizzy and motion sick. Motion sickness is, in most cases, a mismatch between visual and vestibular inputs that the brain can’t reconcile. The result is we feel sick because of the uncoordinated inputs. That’s bad when our life depends on keeping the top of the wings away from the ground.

An Instrument

In a plane, there are many different instruments. There is an attitude indicator (sometimes called an artificial horizon), a turn-bank indicator (and coordinator), a directional gyro, and a compass. These all provide information about the tilt of the wings, left to right, and which way you’re headed. Similarly, the attitude indicator, altimeter, and vertical speed indicator provide input about the distance between the ground (terrain) and the aircraft – and how it is increasing or decreasing.

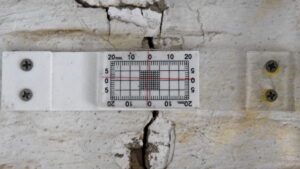

Any individual instrument in the aircraft can – and does – fail. Many instruments are driven by gyros, and those gyros will, over time, wear out and fail. Pilots are taught to expect these failures and cross-check instruments with one another so they can detect a failure in one instrument. The directional gyro is quicker and more reliable than a compass (particularly at high angles of pitch), but it’s always good to check it against the compass, which works on totally different principles and likely won’t fail at the same time or in the same way.

Instrument failures are rare, but they happen. Multiple instruments failing simultaneously in a way that gives bad input is exceedingly rare, but too often, people trust their instincts instead of the instruments.

The Instrument Cluster

There are numerous notable deaths where the flash of the strobe light inside of a cloud disoriented someone, and they started trusting their intuition – instead of trusting the instruments in front of them. Discounting one instrument (or even two) is fine, but when multiple instruments are telling you one thing, and you’re feeling another, your feelings are wrong. If you want to survive, you have to trust – and verify – the instruments.

Change Instruments

In your change project, what are the instruments that you can trust? They’re the metrics that you’ve identified. With a mixture of leading and lagging indicators, you’ve got different approaches to ensuring you’re on the right course. By having multiple different measurements about leading behaviors, you have even better data to understand your course. The difference with change projects, however, is the metrics can often be in conflict.

Metrics in Conflict

In change projects, some metrics may be saying everything is fine, while others may be indicating a problem. An aircraft can have only one objective orientation and position in space. Change projects are much more fluid. That doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t trust the metrics. It means that you should cross-check them and make an assessment – based on the metrics more than your intuition.