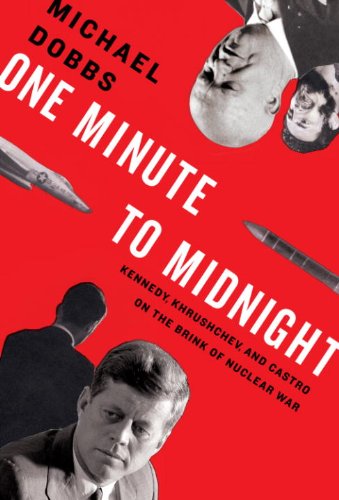

One Minute to Midnight

It was the closest that the world had ever come to a global nuclear war, and it started in America’s back yard. Metaphorically speaking, it was just one minute from the end of the atomic day. The clock advanced to just one minute before midnight, a whisper from the end of the world. Then slowly, magically, it receded to a spot where both sides stepped back from the abyss and found a way towards peace. It was a peace that would start the world on a track of lower risk of mutually-assured destruction.

The time spent one minute from midnight started from October 16th, 1962, when the President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, was notified that we had aerial reconnaissance confirmation of Soviet missiles in Cuba. The Cuban Missile Crisis had begun, and it had the effect of advancing the atomic clock to One Minute to Midnight.

The Story

In brief, the Soviets had worked with Cuban leader, Fidel Castro, in a partnership that put medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) on Cuban soil aimed at the United States. Castro has suffered intrusions into the Cuban state through US-sponsored incursions, most notably The Bay of Pigs. The relationship with the Soviet Union was a way of protecting himself from the US and at the same time allowed Nikita Khrushchev a way to give the US back some of what it was giving to Moscow. The US had deployed MRBMs to Turkey – roughly the same distance to Moscow as it was from Cuba to Washington, D.C.

The situation was ultimately resolved through a blockade and subsequent diplomacy, but not before having nearly two weeks of very tense moments. The missiles were removed from Cuba and the US agreed to remove the missiles from Turkey.

That’s the history lesson and the context of the book. However, in addition to the twists and turns the story takes, there’s a second story that’s told of how our world has changed and how it has stayed the same.

Communications

Perhaps the most striking observation was the change in communications from then to now. Commands relayed from Washington could take 6-8 hours to make it to the commanders of the Navy stationed in the Gulf of Mexico. Official communication to the Soviet Union could take 12 hours or more. Even before the red phone was installed to provide direct communication between the US and the Soviet Union, we had improved communications dramatically.

Today, we take for granted that we can reach out and contact anyone on the planet in a matter of minutes if not seconds. We have video calls with friends and colleagues half a world away. We expect that our messages will arrive nearly instantaneously and that everyone has access to the internet in one way or another. However, at the time, the internet wasn’t a thing. It wasn’t even a wish.

One of the major challenges for the Soviet submarine commanders was the requirement that they surface to communicate with Moscow each day. While the timing made perfect sense in conflicts centered around Moscow – midnight – it made them very vulnerable during the daylight in the Atlantic waters.

Time and Distance

Never had the Soviet Union deployed ships and troops in such quantities so far away. Simple challenges like communications seemed onerous until they needed precise time signals that were too weak to receive from Moscow. Instead, they had to accept their time signals from US sources – unbeknownst to the US army.

Intelligence

It took nearly 30 hours for the US to notice that the Soviet ships that were on their way to Cuba to turn around and start heading home – after the initial awareness that the US knew of the missiles and Khrushchev started pulling back. Still, there was a spy providing the US with lots of useful information including the technical manual for the missiles being deployed to Cuba. We also had a sophisticated (for the time) set of listening posts that made it possible to detect the location Soviet submarines without their knowledge.

Spy planes, including the U-2, were used to gather aerial reconnaissance. (See The Complete Book of the SR-71 Blackbird for more about spy planes.) Where now we have satellites orbiting to safely photograph locations of interest, back then, we had to put people at risk to gather the photographic intelligence we needed to make decisions.

What we knew was mostly wrong – particularly as it pertains to the number of nuclear warheads that were in Cuba and the troop deployment. Moreover, we had dramatically overestimated the Soviet nuclear capacity. Where we underestimated the deployment strength, we vastly overestimated the total strength.

Missiles

The crisis wasn’t really about the ability to hit the US from Cuba. The truth was, as Kennedy was aware, that you were dead whether the nuclear warhead was delivered through an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) or a MRBM. Kennedy never liked the Jupiter missiles deployed to Turkey and he tried to remove them – but he was always blocked. His “ace in the hole” was the Minuteman ICBMs that were scattered throughout Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakotas. Where the Jupiter missiles were mounted above ground and took 15-30 minutes to fuel, the Minuteman missiles were in underground silos and were ready to launch “within minutes.” Their farm configuration – which spread the missile silos over large areas of sparsely populated space – made them difficult for the Soviets to wipe out in an initial attack scenario.

The missiles in Cuba were a pawn of the much larger nuclear one-upmanship that the two superpowers had been playing. It was the case of American imperialism against communist solidarity. The missiles weren’t the point – the fact that the US was being threatened was.

Cuba’s Castro

Ninety percent of Cuba was owned in some way by the United States companies or individuals before the revolution. Cuba’s liberation meant that the government ceased the assets of foreign owners for state control – and even despite this grab of economic power, the country nearly collapsed. Castro’s revolution was a success – barely – but his economy was a wreck. He was intent at doing whatever it took to ensure that the economy survived, so that the country would survive under his leadership.

He was, however, a revolutionary at heart, and as such, he was willing to go to much greater extremes than either the US or his Soviet counterparts. Where the US soldier wouldn’t tolerate poor conditions and as much as one-third of the soldiers becoming ill, this was tolerable for the Soviet troops. The Soviets had done testing on their own people with regard to the impacts of nuclear radiation. Many died as a result of their radiation exposure. Castro knew the impacts of nuclear radiation and was willing to poison his country for decades to stop an invading US force.

The Soviets brought more with them than the MRBMs. They brought tactical nuclear weapons that would wipe out an invading force – but not without rather permanent and lasting damage to the ability for Cuba to be habitable. This didn’t seem to bother either the Soviet suppliers or the Cuban Dictator, who seemed locked in his revolutionary ways and the belief that winning was all that mattered.

The Consequences of Nuclear War

Kennedy and Khrushchev were both painfully aware that there was no such thing as a limited nuclear war. They knew that once the first weapon was fired (even inadvertently), there would likely be little turning back. Where Castro seemed intent on using whatever means necessary, both leaders saw their roles in history differently. They felt like that if they stepped too far forward, there would be nothing to step back to.

What does it mean to be the victor when the world is destroyed, they wondered. Victory is hollow when it is only to survive longer before inevitable death.

Communism

The threat to democracy was communism. There was a belief that it just could be a better system of government, and the US’ democratic approach was bound to be buried by communist efficiency. Where Khrushchev made promises to crush the US economically, we now know that this was just bluster. That didn’t stop the inquiries at the time or the fear that our way of living might be changed by forces outside our control.

It’s interesting to me as I compare it to Microsoft’s response to Linux in the 1990s. Linux was a real threat to Microsoft’s Windows desktop market – only to be revealed to be a non-issue. Microsoft did lose some market share to Linux in the server market, but this was hardly as pervasive or as redefining as it was anticipated to be.

When you’re standing too close to the problem, you fail to put it into a proper perspective.

Kennedy

JFK is a hero. However, his image is much larger than the real-life person. His handling of the crisis, his push to the Moon, and his famous speeches anchored a place for him in the American psyche. Having been assassinated, he didn’t have to accept the messiness of the fall from grace. However, when you look deeper, you see parts of the man that don’t reflect the hero image.

His medical issues were a secret to me until One Minute to Midnight. I never realized all the care that he was receiving behind the scenes to remain functional. I recognize these host of problems as the result of stress and incongruency in his world – something that the doctors at the time didn’t appear to be aware of. However, the man that spoke for everyone in America was as fallible as any other man.

There are the stories that you hear about JFK and his infidelity. Marylin Monroe’s relationship with him – including the alleged sexual relationship – are well known. His string of sexual encounters was also well established. However, the relationship with his former neighbor and former wife of a senior CIA official was an aspect I had not previously been aware of.

I can only believe that these were different times for different people, when it was expected that men, particularly powerful men, would have affairs. I don’t understand it or how it would be acceptable to the wives, but it’s far from the last time that a politician – or sitting president – would have an indiscretion that the wife knew about and either condoned or concealed. (Think Bill Clinton.)

I don’t know that we’ll ever get to the same place that we were with the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Soviet Union’s attempts to keep pace with the US economy and defense spending broke it. Communism, it seems, wasn’t as great as it was made out to be. What I do remember from my history class is that those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it – and not just the high school history class. If for no other reason than avoiding the possibility of nuclear war, perhaps it’s time to give some thought to One Minute to Midnight.