Bowen Family Systems Theory in Christian Ministry: Grappling with Theory and its Application Through a Biblical Lens

It’s not always easy to integrate psychological theories into Christian ministry. Bowen Family Systems Theory in Christian Ministry: Grappling with Theory and its Application Through a Biblical Lens is an attempt to address apparent concerns between Bowen’s theory and biblical principles.

I’ve covered the core of Bowen’s theory in Family Evaluation. If you’re unfamiliar with the theory, I’d recommend you start there.

No Blame

Fundamental to Bowen’s view is systems thinking, where everything is related to everything else and therefore there’s no one person to blame. It’s not one thing but the interaction of several that leads to the outcomes.

Finding people to blame is a way to escape accountability. If it’s their fault, then it’s not our fault. But in an interrelated systems approach, it’s not as simple as that. It’s not blame or fault that is important. Instead, the focus shifts to how the interactions lead to negative outcomes and what can be done to get better outcomes.

Everyone Can Change the System

The systems approach means that any component of the system can change and potentially have very large effects on the outcomes. (See Thinking in Systems for how.) Edward Lorenz’s 1972 paper, “Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas?” was a wakeup call to systems complexity and sensitivity to initial conditions. (See Superforecasting for more.) Generally, we think in terms of cause and effect. We expect that the results we receive will be proportional to the amount of effort expended. This perspective is what most of us experience in our day-to-day lives.

However, systems aren’t always like that. Lorenz exposed that it’s possible for very small changes to lead to very large changes in the output if the system is sufficiently unstable. When we live in a world identified as VUCA – volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous – we’re in a system with inherent characteristics of instability. We can, from our position – no matter what that is – impact the entire system.

No one expected that Twitter would cause radical change in the Arab world – but the First Arab Spring proved that social media can change governments, as it did in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen. Certainly, the change required thousands of protestors and sustained effort – but someone was the first person to stand up and to get the ball rolling.

Simultaneously, we can only guarantee that we’ll be able to change our own behaviors. We can’t insist that someone else will do something to support our change in the system. We get in trouble when we expect that our desires are the desires of everyone.

Hopelessly Entangled in Subjectivity

In any place where openness and honesty are valued, there is the opportunity for learning. However, that learning comes far less frequently than all of us would hope. Instead, we find Cass Sunstein’s concern that we’re Going to Extremes. We find that we can’t seem to listen to other people’s data, facts, and opinions. Thomas Gilovich in How We Know What Isn’t So explains that we ask different questions about data depending on whether it aligns with or contradicts with our worldviews. Congruent ideas are asked if they can be believable. Incongruent ideas are subjected to the must harder standard of must we believe them.

Genogram

Bowen didn’t use the term “genogram,” which was coined by others, but he started counseling with a visual diagram of the family. The basic notation uses squares for men and circles for women. Lines connect couples and their children, which are drawn beneath the couple, creating a form of family tree.

The basic approach has been used for dozens of purposes, including in healthcare to track the genetic progression of risk factors for disease between generations. In Bowen’s use, he was looking for patterns of family relationships that might have been transmitted.

Like all forms of visual representation, the goal is to make it easier to understand where the person is today based on their history and current reality.

Lifelong Quest for Maturity

Bowen’s perspective was that individuals could elevate their differentiation and overall maturity, but that this was a slow and lifelong effort. He viewed the work of family diagraming as one step for creating self-awareness. This exposes a dialectical aspect of Bowen’s work.

On the one hand, he believes that it’s the relationships and interactions that drive the function or dysfunction; on the other, individuals have the capacity to bend the arc of outcomes in a positive direction by better understanding themselves and responding from places of better differentiation of self. While Bowen’s not prescriptive of the kinds of activities that can improve self-awareness, he does encourage it.

Functional Style

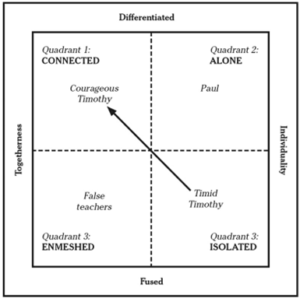

Quoting Richardson, there is reference to a functional style set of quadrants with continuum of togetherness and isolation in contrast to differentiation and fusion – see below.

The core of the diagram is navigating the space between individuality and togetherness. I am concerned about the graphic, because it is expressed as a stable system, but the system itself is inherently unstable. People don’t occupy an individual side or a togetherness side. In some aspects of their life and at some times in their lives, they’re more moved towards individuality; in other times, more towards togetherness.

Let’s take, for a moment, Erikson’s stages of development. The idea of individuality appears in several stages. (See Childhood and Society.) One could argue that individuality is a plague upon our current times, but Robert Putnam’s research both in The Upswing and the older Bowling Alone don’t bear this hypothesis out. Francis Fukuyama in Trust talks about how individuality impacts (and is impacted by) trust. I mentioned in my review that even the relatively closed-community Amish expect a period of individuality and separation from the community called Rumspringa.

Looking at it less temporarily and more relationally, we often want togetherness in places and individuality in others. There may be people who are lone wolves at work but who surround themselves with friends or family – or both – whenever they’re away from work.

From my perspective, this means that even defining areas of movement in this quadrant system would be difficult to justify. There are just too many important dimensions that are lost using this framework.

Rescuing or Relational

As a pastor (elder, deacon, or human), do you see your role as rescuing those you come in contact with – or being in a relationship with them? It’s a subtle but fundamental difference. From a Christian perspective, it’s Christ that saved us – none of us humans are capable of that. What Jesus did that we can do – and what we’re called to do – is to be in relationship with others.

It’s the fundamental reframing that Carl Rogers implored us to make. Instead of presuming expertise over someone’s life, acknowledge that they are the experts in their lives. While we may bring some things to the table in terms of our experience, knowledge, and even wisdom, we are not experts in someone else’s life. However, we often believe because of our position, our credentials, or our ego that we should take up position of power over someone. What we too frequently forget is that we’re with others – not over them.

Unity and Diversity

Organizations naturally prefer unity and rarely achieve it for long. However, that’s a good thing. If we are always in unison, we can fall victim to groupthink, Irving Janis’ term for when groups are so unified they make poor decisions – or fail to recognize the need for change. (See Decision Making.) Richard Hackman, known for his work on collaboration, explained the “Goldilocks paradox” of having just the right amount of unity. Scott Page in The Difference and Adam Grant in Originals explain how diversity of thought, history, and perspectives can be essential to good decision making.

If we have too much unity, the organization calcifies. If there’s not enough unity – if there’s too much diversity – the organization flies apart. The secret is to live with the tension between these two extremes and find oscillations in the middle that can drive change and allow for the efficiencies of unity.

I think there’s much more that we can learn from Bowen Family Systems Theory in Christian Ministry – beyond the Christian ministry context.