The Complete Book of the SR-71 Blackbird

My reading list has been described by many, including my wife, as positively boring. I read about so many topics that most people would use to put themselves to sleep. However, this book is different. This book is about my positively all-time favorite aircraft. It flies (or flew) faster and higher than missiles. Growing up, I’d hear stories of the “Blackbird” and I was in awe. That’s why I read The Complete Book of the SR71 Blackbird – but there was a twist.

The twist was that I needed to verify a comment that I had heard long ago. That comment was that the SR-71 leaked fuel like a sieve while on the ground. There was some discrepancy about whether that was truth or not, so I had to find out for sure. But before I get there, I should explain how the airplane came to be.

Russia and the U-2

It was 1956 and Kelly Johnson’s team at Lockheed had created the most sophisticated reconnaissance plane ever known: the U-2. It flew so high that it was thought that ground-launched missiles wouldn’t be able to reach it – at least for a few years. It was only a few years later (1960) that a U-2 was eventually shot down inside of Soviet airspace. It was quite an incident in Cold War history. However, even before the U-2 was shot down, Kelly Johnson’s team was at work on the successor.

If you know your aviation history, then you know that Kelly Johnson took a team aside and separated them from the main bureaucracy of Lockheed, and ultimately took on the moniker of Skunk Works. This was an adaption from the comic strip Li’l Abner, by Al Capp, where Skunk Works was a dilapidated factory. The advanced development program’s (ADP) initial location was near a malodorous factory, and eventually the combination of the smell and the popularity of the cartoon caused the nickname Skunk Works to stick.

The initial aircraft from which the SR-71 was adapted was the A-12. This was to be the replacement for the U-2. Instead of just staying one step ahead of the enemies, Johnson and the team decided to innovate in multiple areas to give the aircraft the ability to be serviceable for the long term. They did that. The first flight of the SR-71 was December of 1964, and its last military operational flight was in 1997. A 33-year run for a spy plane is beyond impressive: it’s unprecedented.

Higher, Faster, Less Visible

The way that the aircraft managed to be serviceable over such a long period of time was that the innovations drove it in three key areas.

First, the aircraft had a very high operational altitude. In fact, the service ceiling was 85,000 feet. This is well into the stratosphere and the limit for the range of jet-powered aircraft. Missiles had an effective operating ceiling of 60,000 feet. In short, the SR-71 was designed to fly higher than missiles could reach.

Second, the aircraft holds the speed record. Operational maximum cruise was Mach 3.2 (3.2 times the speed of sound). Speeds more than Mach 3.2 were possible by the SR-71; but due to heating of the skin of the SR-71, speeds above Mach 3.2 were rare. Even against the fastest-moving and longest-range contemporary missile, the Soviet R-37, the missile must be fired within 185 km to have the slightest chance of hitting the SR-71. The missile travels a maximum range of 400 km at speeds up to Mach 6. This assumes that the firing aircraft is at the same level of flight and that the SR-71 isn’t over the service envelope of the missile.

Third, the SR-71 pioneered stealth technology. It’s the original way to be less detectable to enemy radar. Its body and coatings gave it 1/10th the radar signature of a F-15 fighter. Even if the missile could get as high as it was flying, and managed to catch up with it, it would have to find the SR-71, which wasn’t going to be an easy task.

These advances made the SR-71 an aircraft that was never shot down by an enemy. Every loss was due to mechanical failures or pilot error. That’s impressive for a fleet of aircraft that logged over 11,000 mission flight hours – and a total of over 53,000 total flight hours.

Vulnerabilities

However, ultimately, the SR-71 was vulnerable. It was vulnerable to politics, budgeting, and the perception that it was cheaper to gather reconnaissance from satellites than from the SR-71. The aircraft that was never shot down ultimately was shut down. In fact, the program was shut down twice. In 1997, the program succumbed to political pressures and funding issues.

Other aircraft and drones were delivering real-time reconnaissance and the SR-71 could not. Its systems were never updated to support real-time transmission of data, and the lag in getting the data back from the aircraft became increasingly untenable in a world where we wanted the information now.

Satellites and drones didn’t risk human life, and they provided quicker access to the intelligence that the military community was now demanding. Besides, the cost of the custom JP-7 fuel was expensive.

Leaking Like a Sieve

To make the SR-71 work, there were numerous challenges; but none more impressive than designing an engine that would work like a jet on takeoff and transition to a ram jet engine in flight. Put simply, a jet uses a fan to compress air and create the literally explosive thrust. Once you exceed a certain speed, this isn’t efficient any longer and it’s not necessary. It’s possible to use aerodynamics to create pressure through the air coming in.

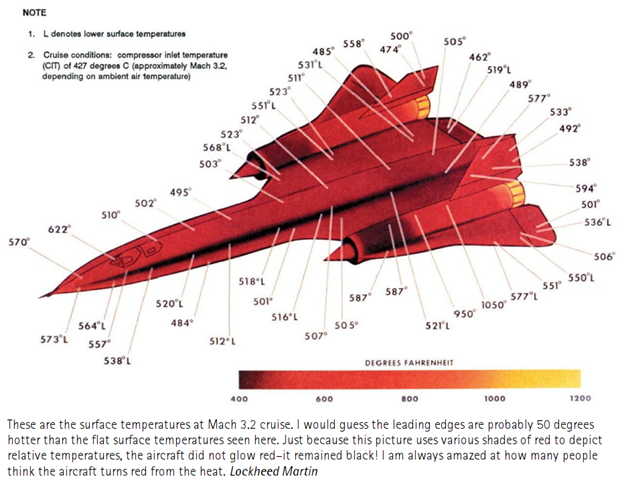

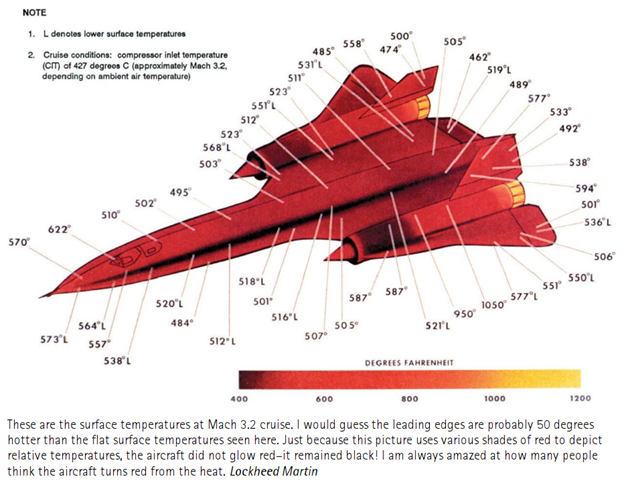

The other interesting aspect of the engine is that it needed a fuel source with a very high ignition point. Flying at Mach 3.2 – no matter how high you are – creates a great deal of friction that will heat the skin of the aircraft. Look at the following figure:

The SR-71 needed a fuel that didn’t have a low flash point. Thus, the development of JP-7, a fuel unique to the SR-71. This higher flash point required an ignition system that leveraged Triethylborane (TEB) which explodes in the contact of air. So in addition to the JP-7, the SR-71 had to have TEB to ignite – or reignite the engines should they stall. In addition, even with JP-7, it was necessary to fill the fuel tank voids with nitrogen to prevent oxygen getting in and creating the opportunity for the JP-7 to ignite.

The net effect of the need for such a high temperature aircraft would mean that there had to be a plan for things to expand during flight, both due to the lack of atmospheric pressure but also due to the heat on the surface of the SR-71. While on the ground, the JP-7 would leak out of many small gaps in the tanks. Thus, the comment that the SR-71 leaked like a sieve on the ground. In the air, these small gaps closed as the materials heated and expanded.

I was looking at my photo for describing the SR-71 in my presentations and realized something very odd that was only apparent to me after seeing other photos in the book. Take a look.

I didn’t initially understand the lighter colorings on the top of the wings, until I realized that this flight, obviously going more slowly so that it could be photographed, was showing the JP-7 getting siphoned out the top of the tanks on the SR-71 by the low air pressure on the top of the wings. The SR-71 leaked like a sieve when it was cold – not just on the ground.

A Dream

I don’t have a prayer of flying an SR-71. Even if the program were still in operation, the people that had the opportunity to fly the SR-71 were the absolute best in the aviation business, bar none. Though it lacked the action that some pilots longed for, it was still an assignment that a select few would be allowed to get. The requirements physically, as a pilot, and psychologically were immense. I have deep respect for those who had the opportunity to fly her.

I’d love to just fly the simulator of the SR-71. While, undoubtedly, I’d not do well, just experiencing what it would be like to be flying in the fastest aircraft ever made would be worth the embarrassment of not doing it well.

The story that I remember most was the one from the reconnaissance mission over Libya after the US had bombed terrorist training camps of Muammar Qaddafi. The SR-71 was piloted by Brian Shul, and it completed its mission despite being fired at by some surface-to-air missiles that we hadn’t knocked out. He literally completed his reconnaissance pass before punching the throttle forward to outrun the missiles. He reported that the aircraft achieved Mach 3.5 while evading the incoming missiles at 80,000 feet.

This story (or the initial reports of it) created dreams of fast flying aircraft that were invulnerable to enemy defenses. It was then that my fascination with the SR-71 Blackbird took hold. It’s 30 years later and I’ve finally read the rest of the story. I’ve finally read The Complete Book of the SR-71 Blackbird. It might have removed the mystery from the aircraft, but it still hasn’t removed the wonder.