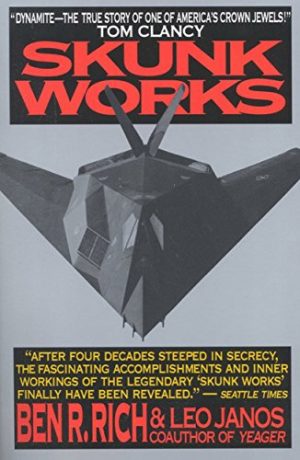

Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed

I’m still in awe. I’m in awe of the organization that was the Lockheed Skunk Works. Ben Rich – who took the helm after Clarence “Kelly” Johnson – mixes personal stories of triumph and frustration into a compelling read in Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed. I’ve made no secret of my love for the SR-71 Blackbird. (See my review of The Complete Book of the SR-71 Blackbird.) However, what I couldn’t fully convey is my appreciation of the organization that created it – and much of the technical wizardry that moved us from late to the game to generations ahead of the competition. What Johnson and Rich accomplished at Skunk Works is simply remarkable by any measure.

Kelly Johnson

The stories of Kelly Johnson are remarkable. He was willing – sometimes too willing – to go toe-to-toe with generals and as quiet as a jet engine about getting what he felt he needed – and only what he needed – to be successful. With credits for the first US Jet fighter, the first super-sonic jet fighter, the U2 Spy plane, and the SR-71 Blackbird, he was the preeminent aerospace engineer and businessman of his era. No one could touch his results – and it’s a good thing, because he needed the results to keep people working with him.

The Skunk Works started without its nickname in a rented circus tent next to a plastics company, whose noxious smell would keep the undedicated but curious away. It was about that time that cartoonist Al Capp named an outdoor still in one of his comics “the Skonk Works.” The cartoon made its way to the tent, and it led to the new name for the secret team working on America’s first jet fighter.

Ben Rich recounts the technical skill of his predecessor and friend. Kelly, it seems, intuitively knew how things would end up. He’d estimate the results of complex calculations that would take Rich or the team hours to do. The world before computers, the calculations were done by hand, and that took time. Armed with his trusty slide rule but rarely bringing it out, Kelly had developed a feel for how things worked. (This is the kind of experience that Gary Klein would discover in fire commanders and other experts. Find out more in Seeing What Others Don’t.)

U-2 (Not the Band)

Before Johnson left the helm in Rich’s capable hands, the U-2 spy plane was already flying. Its advantage as an aerial reconnaissance plane was the fact that it had a service ceiling (maximum flight altitude) of 70,000 feet. None of the airplanes or surface-to-air missiles at the time could reach it at that height. It gave the United States the ability to spy on the activities of Russia with impunity until a fateful day in 1960, when Russia was finally able to down the U-2 piloted by Gary Powers. In the four years since its first flight, the U-2 had revealed the true scope of the Soviet threat and invaluable intelligence on what they were up to.

Shortly after the U-2 entered service, it was clear that it was just a matter of time before the Soviets would be able to shoot it down. It was at that time that the push came from Kelly to create an aircraft with an even higher service ceiling and, more importantly, was much faster. Where the U-2 cruised sub-sonic, the aircraft that would eventually become named the Blackbird would travel at three times the speed of sound.

Rich the Technician

While a substantial portion of Skunk Works is dedicated to his time as a leader of the organization, he had to prove his technical chops, and the place where this really shone was in propulsion. In the end, he was able to create the engines and engine control systems that allowed the Blackbird to fly. They weren’t perfect by any stretch of the imagination, only being 84% fuel efficient – however, that was 10% better than any other design at the time, and it was good enough. The pilots hated the unstarts that happened when the engines stalled, the fuel special to only the Blackbird, and all sorts of the other special requirements, but the engines could maintain Mach 3 at 80,000 feet. It’s something that we’ve never repeated in any other aircraft. (See The Complete Book of the SR-71 Blackbird for more on this amazing aircraft.)

The Age of Stealth

The Blackbird was already a stealthy airplane. Its radar signature was more akin to a Piper Cub than the 140,000-pound, 108-foot behemoth that it was. It was bigger than it looked on radar, but radar could still see it. (Besides, Piper Cubs don’t fly at 80,000 feet!) The next challenge was to make an airplane that was effectively invisible to radar. For that, the Skunk Works got a bit of accidental help from Moscow. Pyotr Ufimtsev, the chief scientist at the Moscow Institute of Radio Engineering, authored a paper titled “Method of Edge Waves in the Physical Theory of Diffraction.” It held the secrets to stealth with a set of equations that predicted the amount of energy that would be reflected to the source based on the shape of the object.

This was the second time that Russia had helped our efforts. Through much misdirection, the CIA had managed to acquire most of the titanium needed for the Blackbird from Russian suppliers when the US supplier couldn’t produce enough.

These advances in stealth technology were easily as important as the advances that the Blackbird brought to aviation. It would take a great deal of risk, immense courage, and determination, but the results would be worth it.

Hopeless Diamond

Armed with a primitive computer and equations, Denys Overholser would come up with the shape that would be called “the Hopeless Diamond.” It looked nothing like something that would fly, and the fellow engineers at the Skunk Works were quick to point that out. However, in the end, the team knew that stealth would be the name of the game, and they reluctantly agreed to make it work – if the predicted radar signatures could be produced.

In test after test, the design met the radar signature goals. From wooden models on poles making it clear that the poles had a higher radar signature to actual flight tests where radar technicians couldn’t find the aircraft at all – even when they were told where to look – the Hopeless Diamond became the aircraft named “Have Blue” and eventually the F-117 Nighthawk Stealth Fighter.

In the end, the stealth work was so effective that the helmet that the pilot wore had a bigger radar signature than the aircraft itself.

Have Blue (F-117)

It was eight years after initial operating capability that the F-117 would prove its worth. It was still an ugly aircraft to most people. Even though Johnson pushed Rich away from the aircraft for some time before finally being convinced, Johnson and the aircraft had something in common. They both delivered results and, in the end, that’s what mattered. It took the Gulf War in 1991 to demonstrate the power of a stealth aircraft with precision bombs.

Until then everyone had to rely on tests and the dead bats in the hangars. That’s right, the bats were running directly into the F-117 and falling dead. The aircraft was difficult to see, even to bats’ echolocation system.

Air Superiority in Baghdad

At the beginning of the war, Baghdad had more protection than Moscow, with some 16,000 missiles and 3,000 antiaircraft emplacements. It was designed to be a fortress. The generals planning for the gulf war had to wonder how long it would take to grind down the air defenses such that the full stage air combat and domination could begin. The planners worried about what the losses of aircraft and personnel would be to acquire the air dominance they needed to win the war. They didn’t have to wait long.

At 3AM local time on January 17, 1991, the power of the F-117 was clear. The first wave of ten F-117 arrived at Baghdad to blind firing of the antiaircraft emplacements. They were blind firing because they knew something was coming, but they couldn’t tell where it was. The second wave of twelve fighters came in an hour later. With the support of a handful of Tomahawk missiles, Iraq was out of the war on the first night. Their communications centers were in rubble, and major strategic targets like power generation were already offline.

Through the entire course of the war not one F-117 aircraft was hit by enemy fire. When you expect to lose 5-10% of your aircraft in the first month, losing none sends a powerful message. The combination of stealth and smart bombs could not only hold their own, they could make it safe for the rest of the air force to fly.

Support

The video of bombs destroying their targets made for great public relations and great television. Small delays might have been required to let the Iraq anti-air defenses to overheat their guns and become vulnerable, but eventually they all did. They all succumbed to the precision bombs that the American public would watch with their evening news. Pilots would brag that commanders could tell them whether they wanted a bomb in the men’s room or the lady’s room, and they’d oblige. Sure, they were confident, but with their success, you couldn’t blame them.

The Challenges of Success

The Skunk Works had done it. They had demonstrated air superiority time and time again. However, this set the stage for some startling losses – not from our enemies overseas but from our own politicians.

It pains me to say that the SR-71 is no longer in operation. It was the victim of politics. Though it was described as too expensive and unnecessary, it filled an operational niche that hasn’t been filled. If you want to get a picture of an enemy position at a specific time of day, you could have it. While satellites provide reconnaissance, they don’t give you the ability to pick the time. You have to wait for the next overpass – and hope that there isn’t a cloud over the one piece of real estate you really care about.

There were other projects that were scuttled because they didn’t seem to make sense. The stealth direction was great, but the move towards unmanned drones continues. Even failed projects like Tagboard, which was designed to use drones to spy on enemies, leave a legacy.

The problem when you build technology so substantially superior to your competitors is that you don’t have anything left to innovate on, so the teams that created such amazing airplanes are forced to look to other ways of keeping in business. The things that make stealth so amazing also don’t help your career if you’re looking for the next star on your lapel. It’s better to command more people and equipment – that you can talk about – than it is to own the program that will allow you to own a war.

Projects like stealthy ships never made it to be a substantial part of the arsenal. Instead of working on the strategically important projects, people at all levels chose projects that would provide some level of advancement while being much more visible. The result is that the operations at the Skunk Works aren’t what they once were. While I’m sure there are classified projects going on at Skunk Works that weren’t discussed in the book, Rich makes an important point that the things that were classified in 1964 probably aren’t worth knowing about in 1994.

The Skunk Works was an amazing place at the time. While I’m sure it’s still great, I can’t help but think that, without challenges to address, it won’t be the same.