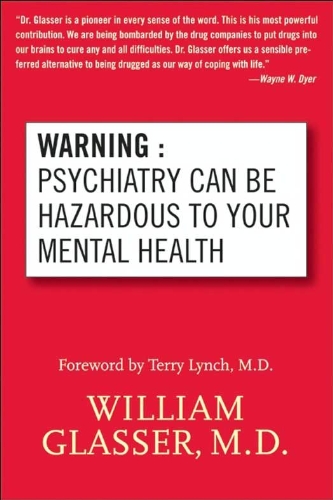

Warning: Psychiatry Can Be Hazardous to Your Mental Health

It’s an odd title for a book. Why would a psychologist title a book Warning: Psychiatry Can Be Hazardous to Your Mental Health? The answer lies in the belief that drugs are not the answer to all of the mental health problems of the day, and that in truth many – if not all – of the mental health problems that we have today can be traced back to a single source: unhappiness. While happiness itself is hard to define and even harder to find, the lack of happiness seems to manifest problems in our mental states as well as our physical bodies.

Dr. Glaser has written several books including two books that I’ve previously reviewed: Schools Without Failure and Choice Theory. Fundamentally, Dr. Glaser believes that we all have choices to make, and it’s understanding those choices that frees us from the bonds of unhappiness. Here, he extends his views into the ills of psychiatric drugs.

Placebo

I’ve addressed before the powerful effects of placebos and my belief that they’re driven by hope. (See The Heart and Soul of Change.) Dr. Glaser shares that, in some studies, patients who were getting better immediately relapse when they’re given the news that they’ve been receiving a placebo. It’s too difficult for them to accept that they were getting better based on their beliefs not on an external drug. Placebos work because we believe that what is being done has the capacity to heal us, to make us better, and to make it alright. If we just take the blue pill, we’ll find that we’re alright soon enough.

While ethicists that I know don’t believe that we should always give patients a placebo and tell them it’s an experimental new therapy that might work in their case, I’m not so sure. Perhaps my ethical boundaries get a bit blurry when we’re talking about eliminating human suffering. Perhaps I’m underestimating the damage to trust that it would do to tell someone they’re in an experimental program. However, I’ve got a strong desire to experiment with how effective I could get placebos to be by infusing patients with hope.

Efficacy

Efficacy is interesting in clinical studies. In order to be significant, there needs to be a sufficient difference between the control group receiving the placebo and the study group that’s receiving treatment. Unfortunately for psychiatric drug manufacturers the placebo effect is quite large. This means that drugs have to show a very high degree of efficacy in order to have a significant effect.

Some studies for some drugs have shown these larger effects, but the effects aren’t nearly as large as people would like you to believe. While drug companies can claim that 50-60% of people taking their wonder drug got better, they neglect to mention that 47-50% of people got better on placebo. Basically, there’s a maximum of a 13% difference – and a mean of 6.5%. A lot of money is being spent on small chances at making things better.

Long Term Effects

What is worse is that the long-term effects of these drugs are known to be potentially very bad. For instance, 25% of people treated for five years with schizophrenia medications will develop tardive dyskinesia, which is characterized by repetitive, involuntary, purposeless movements. Stopping medications won’t stop tardive dyskinesia. Once the damage has been done, it can’t be reversed.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are another class of drugs that, while widely-used, have questionable long-term impact and incredibly short (6 weeks!) studies of their efficacy. (See Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology for more about SSRIs.) Some animal studies have shown the prolonged exposure to SSRIs causes the brain to down-regulate the number of serotonin receptors that the brain has.

Study Sources

It gets worse. The studies that we do have to prove marginal effectiveness of these drugs are sponsored in most cases by the very pharmaceutical companies that want to sell the drugs to the market. While this is in some ways to be expected, because they have the financial advantage if it sells well, it also raises the very real concern about undue influence in the study results.

If you don’t believe it can happen, consider the incorrect link assigned between vaccinations and autism. It was an article in The Lancet has since been retracted: the collaborators on the article indicated that they weren’t aware of the lead author’s ties to a group trying to prove that vaccines were harmful. The lead author, Andrew Wakefield, has lost his license to practice medicine and in professional circles has been thoroughly discredited. However, the myth of the correlation between vaccinations and autism persists. Millions of children each year aren’t vaccinated due to one bad author and the one bad study.

Study Issues

Even if you accept honorable intentions, it’s estimated that 40% of peer-reviewed published research articles contain statistical errors. That’s just statistical errors. That doesn’t account for any leakage of information, accidental bias, or other introductions into the study which unduly influenced the results. If you run enough studies over a long enough period of time, you’ll eventually find a way to prove what you want to prove. Some hidden variable will appear in the data and you won’t be able to factor it out. (See The Black Swan for more on unexpected events.)

Having been in and around the publication of a few studies myself, I can say that all too often what is in the study design and what makes it into the paper is a small fraction of the important factors that led to the results. The reason that folks want multiple studies confirming the same thing is that too often studies are proven to be false or insufficient to demonstrate the effect that was expected.

A Better Alternative

So while insurance companies pay for the prescriptions to these psychological drugs for years and years, rarely do they pay for more than a few therapy sessions. While there is support for a limit to the number of sessions for effectiveness, the insurance minimums are often too short to provide any real impact. Instead the insurance company will pay for drugs for years and years.

Again, my proximity has led me to the awareness that insurance companies don’t expect members to be in the plan long enough to take on substantial upfront costs – like counseling – when low-level, long-term costs are sufficient. In short, they’re willing to keep people on drugs that mask the symptoms rather than solve the root cause, because their cost over the time they expect to retain the member is lower. (Talk about disincentives.)

If people could resolve their unhappiness, they wouldn’t need continuous drugs. In fact, George Brooks found that medication wasn’t enough to allow schizophrenic patients to leave the hospital. They needed psychosocial rehabilitation – at the end of which the drugs were no longer needed.

Let’s Get Together, Yea, Yea, Yea

The theme song for The Parent Trap says, “Let’s get together, yea, yea, yea” and it hides a certain truth: that we are social creatures, and that much of our happiness is gained in our relationships with other people, whether it’s understanding the different levels at which people relate as I discussed in High Orbit – Respecting Grieving or The Gifts of Imperfection.

A Science magazine article indicates that isolation “is as significant to mortality rates as smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity, and lack of physical exercise.” (See The Psychology of Hope for more.) Clearly we have to be in relationship with other people to be healthy physically.

Don’t Worry Be Happy Now

It would be great if it were as easy as deciding to be happy and suddenly you would become happy. It would be amazing to be able to make the decision to transform your life from one of stress and anxiety to one of peace and tranquility. In truth, this is sort of the case. Ultimately it’s a decision to view the world differently and choose different behaviors; however, the process is neither simple nor easy. It’s not as easy to, as Bobby McFerrin says, “don’t worry, be happy now,” but it is possible.

The process sometimes requires the assistance of drugs in the short term to lift someone out of the pit of depression. The drugs provide enough support for someone to do the work to change their perspective. Once sufficiently lifted from the clutches of depression, Dr. Glaser believes in his Choice Theory, which states that it’s our attempt to control others that makes us unhappy.

In short, if we can just allow other people to be separate people, and not try to control them, then we’ll be much happier. Though this is easier said than done, it is something that can be transformational.

Transformational Breakthrough or Emotional Breakdown

Looking from the outside in, it’s quite difficult to distinguish between a transformational breakthrough and an emotional breakdown. The observable behaviors are the same. We see a rapid transformation in someone. Often, there is a lot of weeping and gnashing of teeth in both scenarios. It’s not a pleasant experience. However, after a transformational breakthrough, the clouds part and the skies are bright and shiny. With an emotional breakdown, there’s no clearing of the skies, and often the person feels stuck.

It’s very little wonder that a psychiatrist can’t tell the difference between a transformation and a breakdown. In the appendices, Dr. Glaser provides space for some other authors to share their stories. In one of the stories, a professional shares how he was himself on the wrong side of the profession. He was almost committed by his colleagues and spouse into institutions, and he was able to experience what it is really like to be a patient. His only recourse was to voluntarily commit himself so that he could leave on his own.

The triggering event in this case was really about questioning the path to recovery of patients. In questioning the status quo and transforming his thinking, he was considered to have a mental disease. His colleagues and spouse couldn’t see that he was gaining a new level of understanding – perhaps because this would have meant that they were missing something.

Conversion Disorder

Glaser believes that our psychological ills – our unhappiness or lack of mental health – causes our bodies to react in negative ways. This is consistent with the research of Spolsky in Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. His belief is that many – if not all – of the diagnoses in the DSM-V (DSM-IV at the time of his writing) can be explained by the fact that people are unhappy, and the diagnoses in DSM-V are simply manifestations of that unhappiness.

Many of the non-specific cause illnesses he attributes to a lack of mental health. He suggests that, as people learn to be happier, their physical symptoms will eventually subside. While I am certainly not qualified to speak for every physical condition, I can say that I’ve personally seen remarkable changes with people who have become happier. Their physical issues are reduced.

At the heart of these changes and the increased happiness is a connection with others.

Group Think

One of the interesting structural decisions for the book was that it follows the path of a couple who were struggling with their own selfish and controlling needs through their recovery and sharing their discoveries with a group of their friends in a book club. The structure of the book is different than most in that it follows a story arc from the initial awareness of the ideas to how those same ideas apply to others in different situations.

Ultimately the book seeks to create groups – self-supporting, no-fee groups – that speak about Choice Theory and how it can positively transform lives. While I don’t believe this movement ever gained ground, it is a noble idea. The idea that groups – much like the concept of an AA group – could help improve the health of its members and provide them with the connections they need to become healthier is certainly an idea worth trying.

In fact, just reading and pondering on the thoughts inside of Warning: Psychiatry Can Be Hazardous to Your Mental Health is a worthy endeavor as well. After all, difficult or not, you do have a choice to be happy.