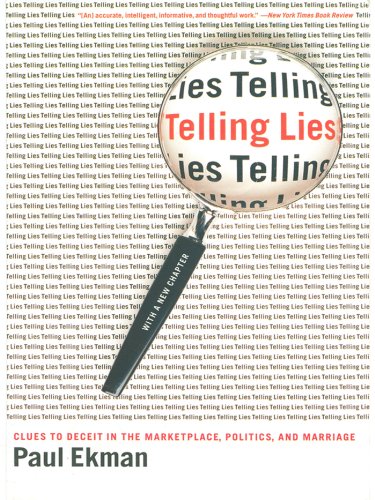

Telling Lies: Clues to Deceit in the Marketplace, Politics, and Marriage

I’ve been a fan of Paul Ekman’s work for some time now. Telling Lies: Clues to Deceit in the Marketplace, Politics, and Marriage isn’t the first book of Dr. Ekman’s that I’ve read. I got exposed to his work through Destructive Emotions and Emotional Awareness, both of which feature his relationship with the Dalai Lama, which has prompted other reading. (See My Spiritual Journey and The Dalai Lama’s Big Book of Happiness.) My fascination with Dr. Ekman’s work isn’t about his work on lying. My interest is in his awareness of microexpressions – small facial expressions that happen involuntarily as an emotion is triggered.

I’ve been on his mailing list for some time. I’ve been intrigued by his involvement at Pixar with the Inside Out movie. (See mention of this in my review of Creativity, Inc.) Recently, he released an autobiography that I read, and he mentioned that Telling Lies was his second favorite book behind Emotions Revealed. Emotions Revealed isn’t available electronically and so I decided to read Telling Lies to see what made the book important.

I don’t condone lying as a rule. I believe that many of the challenges we face as a people are due to what the Col. Nathan Jessep (as played by Jack Nicholson) in A Few Good Men said: “You can’t handle the truth!” As I look through leadership, management, and psychology books, I see over and over again that we create problems when we’re unwilling – or more frequently unable – to be truthful.

What is a Lie?

A lie isn’t exactly the opposite of the truth. To lie, Dr. Ekman explains, is when “one person intends to mislead another, doing so deliberately, without prior notification of this purpose, and without having been explicitly asked to do so by the target.” This definition is effective because it excuses those who aren’t aware that they are misleading someone – if they are themselves being misled. It also exempts actors who we’re all asking to lie to us – after all, few people would consider an actor in a movie a liar because of their role in the movie.

Similarly, when a comedian does a three-step joke (see I am a Comedian for more) he’s not lying, because the audience wants a bit of misdirection so that they can find the error of their ways. (See Inside Jokes for more on how humor works as an error-checking routine.)

Is a Lie Good or Bad?

When your grandma makes a bland, salty dinner, that you eat but certainly don’t enjoy, do you tell her? When you excuse yourself early from a party because it’s boring, do you let the host know why you’re leaving, or do you provide a little “white lie” to spare the hosts feelings? Most of us lie all the time. Our lying may seem harmless, polite, or even compassionate. Lying is a part of life. We all do it. So is it good, or is it bad?

The answer is probably both. Dr. Ekman doesn’t find lying as reprehensible as others do, in part because of examples like the ones I used above. Lying can be humane. He argues that sometimes the person who is being lied to is a willing participant, because they don’t want to know the truth about the lie.

While I don’t share Dr. Ekman’s perspective on lying, I believe that, in truth, all lies have a cost and some of those costs are larger than others; I do accept that there are different kinds of lies and that they have different long term costs.

Types of Lying

According to Dr. Ekman there are two basic types of lying. There is:

- Concealment –A lie of omission or hiding our true feelings, and

- Falsification – Fabricating a false truth

Some people, Dr. Ekman explains, reserve lying for falsification. Others, such as Scott Peck in The Road Less Traveled, call falsification a “black” lie and concealment a “white” lie. Whether you label concealment a lie our call it hiding, it has the same impact of eroding trust. (See Trust => Vulnerability => Intimacy for more about trust.) The difference between the relatively passive concealment and the fairly active falsification might explain why some people reserve the word “lying” for the active state of falsification. Liars feel guilt less strongly when they conceal than when they falsify. (See Brené Brown’s work in The Gifts of Imperfection, Daring Greatly, and Rising Strong (Part 1 and Part 2) for more on guilt, shame and their impacts.)

There are other related approaches to lying that largely fall into the two preceding categories, which are:

- Misdirecting – Acknowledging an emotion but misidentifying the cause;

- Telling the truth falsely – Exaggerating the truth, but doing so in a manner that causes it to be not believed – such as with huge hyperbole;

- Half concealment – Admitting only part of the truth in such a way that the receiver believes it to be the whole truth; and

- Incorrect-inference dodge – Telling the truth in a way that causes the target to believe the opposite of what is communicated.

Catching a Liar

Perhaps the greatest benefit of Dr. Ekman’s research as it pertains to lying is the capacity to detect lying in others (as if we want to know). There are many clues that can be used to identify the potential for liars, but unfortunately there are rarely clear-cut cues which can be used to say with certainty that someone is lying. What’s worse is these clues don’t appear when the person tells a falsehood that they believe. Catching a liar requires a bit of luck and also that the liar knows what they’re doing at some level.

Most folks know that there are two primary ways which truthfulness is measured today. There’s the standard interview, where the subject is given the opportunity to share their story – and hopefully the interrogator can identify issues with the story that expose the liar. The second method in widespread use is the polygraph.

Let’s talk about the polygraph in more detail before talking about how interviewing can be effective.

The Polygraph is Not a Lie Detector

Most folks believe that the polygraph is a lie detector. That is, that it detects that you’re telling a lie. In truth, it’s no more a lie detector than voice analyzers that purport to tell you that someone is lying just by the sound of their voice. These voice-based analyzers don’t measure lying, they measure stress. And stress isn’t an indication of lying, it’s a potential clue.

The polygraph is itself an emotional assessment tool. It measures autonomic nervous system (ANS) responses. These responses are hard to suppress and indicate that some emotion was felt. Unfortunately for the polygraph examiner, there’s very little indication of what emotion was felt. The examiner knows that something was felt, but not what or, more importantly, why.

Why was the Emotion Felt?

At the heart of lie detection is the observation of emotions. Whether it’s a voice stress analyzer indicating different degrees of stress in a voice or the polygraph test wired up to the subject, the measure is one of the physiological impacts of emotion on the body. What Dr. Ekman has been repeatedly clear about is just knowing an emotion happened doesn’t tell you the cause.

The problem of falsely ascribing the emotion to the wrong cause is what Dr. Ekman calls the “Othello error”. This name comes from Othello, who accuses Desdemona of loving Cassio and misunderstands her response. When asked to bring Cassio to testify in her defense, Othello tells her that he has killed Cassio. At that moment, Desdemona realizes she is unable to prove her innocence and becomes emotionally triggered – which Othello ascribes to her love for Cassio.

Falsely Accusing

It’s too easy to say, “he’s nervous because he did it”, instead of accepting that it’s possible that the subject is concerned that they might not be believed. It’s convenient to say that someone must be guilty because of their mannerisms when they exhibit those mannerisms all the time.

The other major concern in lie detection is what Dr. Ekman calls the “Brokaw hazard” after Tom Brokaw, a famous reporter who said that he believed people were lying when they didn’t answer questions directly or provided more information than was requested. While it appears that Tom Brokaw may not have been right that these were signs of lying, like much of lie detection, it could be a marker in some cases. The key here is having a baseline to see if this is different than the subject’s normal behavior.

The Interview

The other popular approach compared to the polygraph for the detection of lies is the interview – or the questioning. This is, by far, a more popular approach, particularly in business and relationships. The interview has two basic methods whereby the subject can be assessed. The most straightforward is to get the subject to admit their guilt or create a story that has obvious structural holes which can’t be explained away. The second method is the observation of the subject, and whether they expose their emotions through facial expressions, body language, or speech.

Facial Expressions

Perhaps Dr. Ekman’s best known work is the discovery of microexpressions, facial expressions that occur for fractions of a second and indicate the emotion we’re feeling – before we’re conscious that we’re feeling it. (See Emotional Intelligence for the amygdala’s shortcut to sensory information for how this can be possible.) His research over the years has demonstrated that there are a set of facial expressions that indicate emotions. Even if the person chooses that they don’t want to display the emotion, they leak it through these microexpressions.

Body Language

We know that much of the emotional context of what we say is said with body language. In natural conversation, we use illustrators to reinforce what we’re saying and emblems. Emblems are well-known gestures that convey information that’s not available in the speech.

Emblems are often suppressed when someone doesn’t want you to know the emotion they’re feeling. They’re sometimes only partially expressed and other times shown outside of their normal position. These are indicators that there may be an emotion that’s being hidden. An example might be a shrug, which means “I don’t know.”, “I’m helpless.”, or “What does it matter?” might be shown with only one shoulder.

Illustrators don’t get expressed partially but instead decrease in frequency when someone is carefully considering their words; someone carefully considering their words may be fabricating a lie on the spot. People who use illustrators frequently are described as people who “talk with their hands.” We’ve joked about friends of mine that if they were handcuffed by the police that they would become mute. If when someone tells you that the fish was big – and raises their hands to show you how big, they’re using an illustrator.

Speech

I’ve already mentioned voice stress analyzers as an alternative to the polygraph. There are changes in a person’s voice that occur naturally as they experience emotions. About 70% of people raise their pitch when emotionally triggered.

Another marker to consider is the degree to which the subject is considering their words. Liars – particularly those who have to make up a lie on the spot – may consider their words more intently than someone who is telling the truth. Abraham Lincoln was quoted as saying that he wasn’t smart enough to lie.

The words themselves can betray the subject. Slips of the tongue may mean something, as Freud suggested – but occasionally they may not. Generally, emotional tirades expose a subject’s true opinion rather concretely.

Words can also betray the person if they get trapped in the logical inconsistencies of their own lies which can’t be explained. This is why one recommended interviewing technique is to act as if you believe the lie, causing the liar to extend the lie to the point where it becomes easier to catch them in the lie.

Another technique for causing subjects to expose themselves is the guilty knowledge test. That is, the interviewer asks something that only the guilty party would know and looks for an emotional reaction. This leverages the speech of the interviewer to trigger an emotional response to be detected via other means. This technique isn’t fool-proof either, since sometimes there is other background or information that the subject processes with the question that can trigger a response.

But How do I Detect a Lie?

You may be saying to yourself that these are all good tools, but how do I go about detecting a lie? The answer is that you can’t – not with 100% accuracy. The best skilled and trained interrogators only get to at best 95% accuracy. The general public (including judges and attorneys) are about 30% effective before training. There are several factors that lead to someone’s ability to detect a lie – or not. Since most lie detection is about emotion, it’s no surprise that the factors for lie detection are factors for whether an emotional response will be triggered.

Here are some of the factors that make it difficult to detect a liar:

- Low consequences – When the consequences are low it’s difficult to arouse a strong emotion.

- Low detection apprehension – When the subject doesn’t believe they can be caught because of their skill or the abilities of the detector.

- High collusion – When the detector is highly psychologically-invested in not hearing the truth, it’s unlikely that they’ll detect a lie even when the clues are present.

The challenge with detecting lies is that there’s no one sure-fire way to detect them all the time. You can create conditions that favor your detection, including lying to yourself about your ability to detect lies or the machine’s ability to detect lies. However, the truth is that detecting liars isn’t easy and it’s not certain. (Though Dr. Ekman has made several training programs available for improving recognition of emotions and detection of lies at http://www.paulekman.com/.)

Stealing the Truth

Perhaps the most interesting component of detecting lies was, for me, the concern that some have that, by being able to read emotions from someone’s face, we could teach people to steal the truth from someone who didn’t want to share it. We believe in a fundamental right to privacy of one’s thoughts, and if Dr. Ekman’s techniques could predict liars easily and read emotions too well, we might peer into the inner workings of others minds in a way that seems invasive to them.

Being a relatively open person myself, I see no reason to be too concerned about people knowing the emotions I’m feeling, but I recognize that the more you know about a person, the more opportunity there is to find something wrong.

In the end, Telling Lies doesn’t teach you how to tell lies. Dr. Ekman explains that it’s unlikely that those of us who aren’t good at it could learn. It does, however, help you understand the process and increase your chances of detecting lies.