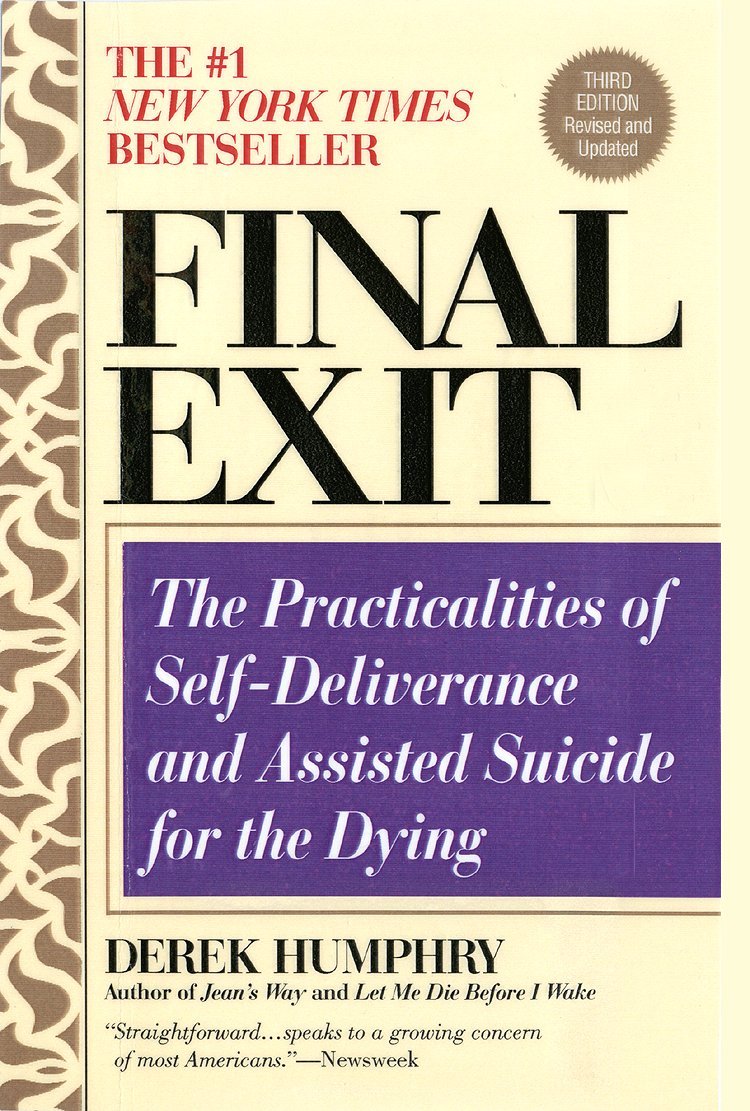

Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying

Some books acquire their own mythology. Groups become so polarized about them that they gain their own mythical qualities. In the space of suicide prevention, Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying has this air to it. It’s a book that many people in suicide prevention won’t get near or read. Some claim that they don’t want to financially support instructions for suicide – others just can’t get past the sticky, taboo feelings. I have no such prohibition. If I am to speak completely and honestly to people who are struggling, I can’t deny or ignore the sources of information that they’ll be consuming. I need to at least understand it, too – even if I don’t agree.

The stumbling path that led me here has me considering After the Ball – a book that I deeply appreciate – and Undoing Suicidism. The latter book is, in part, a manifesto and a call for greater openness to the idea of suicide as an option. It forced me to evaluate under what conditions a society should prohibit and allow individuals of the society to execute their rights – including the right to self-terminate.

Limits

Before beginning, it’s important to note Humphrey’s stated intention, which is to provide clarity and direction only for those he deems worthy of taking their own lives – or at least those who society more or less accepts may take their own life. More specifically, he’s referring to those who are suffering from a terminal illness. He acknowledges that people not in this intended category have used the book, but he takes no responsibility for their use of the knowledge.

A few decades ago, the book may have been the only vehicle to get this information. Tragically, this is no longer the case. Today, there’s no effective way to prevent the same information from being found with an internet search. While this doesn’t support the idea of publishing a book, it is simply an acknowledgement that it’s hard to put all the evils of the world back into Pandora’s box.

I found that Humphrey did wash his hands of responsibility – but not concern. There are, throughout the text, repeated warnings that there are a finite set of people that he’s targeting, and that if you’re not in the target audience, you should stop. While this may prod some to continue, the intent to focus on the terminally ill seems sincere.

A Good Death

Humphrey asserts (and I disagree), “What separates a chosen ‘good death’ from a bad one almost always comes down, upon analysis, to the amount of planning, attention to detail, and the quality of the assistance, all of which are vital to decent termination of life.” First, let me say that while he says “death” here, I believe he’s constrained himself to the type of self-termination that he proposes. That isn’t to say a firefighter who dies rescuing a family or the police officer who saves someone and then, through overexertion, dies of a heart attack didn’t die a “good death.” Where Humphrey is focused, it seems, is upon the certainty of death and the mess that those who are left behind must address.

So, while he describes it as a “good death,” I’d propose a “successful plan.” In the narrowly defined group of people who are making a well-considered, appropriately-consulted plan, I can take no issue that the death should be as certain, pain-free, and lovingly supported as possible. This is at the heart of Undoing Suicidism – and it’s a good point. Should suicide be the last option? Yes. However, that doesn’t preclude it from being an option.

Watching Them Die

Humphrey explains that “it is not a crime in America to watch somebody kill themselves and do nothing to stop it.” In short, some of the concerns that Baril has in Undoing Suicidism – that the person should not be alone – doesn’t appear to be a problem in the US. I can’t say that, even with the precautions that Humphrey recommends, there won’t be some uncomfortable moments and difficult questions when the police arrive – if they do. However, in short, they can’t convict you of the crime of watching a death, because that crime isn’t on the books.

Separately from the legal concerns, there’s the concern of how one will process the death of someone they care for. They wouldn’t be present if they didn’t care, and because they care, there’s bound to be some emotional impact – predicted or not. Most people have never been present when another person dies. It can be a profoundly sacred space – but it isn’t always. Those who choose to watch – regardless of their degree of involvement in assistance to the suicide (or not) – are likely to be impacted in ways that they can’t predict.

Accidents

One of the confounding issues when it comes to gathering statistics on suicide rates is the problem of whether something is an accident or a suicide. In the United States, over 90.7% of vehicle miles traveled are with a seatbelt. Seatbelts and other safety features in cars have steadily reduced traffic fatalities. (See Unsafe at Any Speed.) The lack of seatbelt use in an accident is sufficiently odd that it raises suspicion. (Still, I can say from secondhand experience that this is not always enough to override an accidental mode recorded on the death certificate.)

If someone runs their car into a tree or abutment at full speed, did they intend to hit it, or did they lose control? In the context of Final Exit, what are the chances of survival? The chances for survival without a seatbelt aren’t great. However, from the point of view of Humphry’s framework, it’s unclear how much pain one may suffer before unconsciousness.

Prosecution

Humphrey is careful to recommend approaches that limit the chance of prosecution of those who survive. It includes multiple strategies for demonstrating a clear sense of intent. However, he also offers that close relatives are treated more favorably than friends. (He doesn’t say so, but non-heirs even more so.) He also indicates that less violent means reduce the chances of prosecution.

I think it’s fair to say that most people don’t want to leave problems for those who care about them (and therefore they are likely to care about). The considerations for prosecution are worthy of mention.

Just Stop

Humphrey asserts that, “A willingness to die is insufficient alone to bring about death.” Here, I both agree – and disagree. I’ve seen enough people make decisions to let go of their struggle with their illness to recognize that there’s a set of conditions where the person is being kept alive by their sheer force of will; when it evaporates, their end is near. (My experience is within weeks, if not days.)

Humphrey continues by explaining that someone can’t just “stop breathing.” While he expects that some who are good at meditation might be able to achieve this, the mechanics of brain function are dubious about this point. We’re designed to resume breathing when oxygen saturation in the prefrontal cortex is lowered below the point of conscious thought. However, there are other, more accessible, approaches to biological manipulation that can hasten death.

Mode of Death Certification

Historically, the stigma against reporting suicide as the mode of death has been reported to have depressed the actual numbers of suicide deaths. While the laws that would penalize people’s families for the death by suicide are off the books, the stigma is still alive and well. Above, I mentioned what I saw as a clear-cut suicide, but the mode of death was recorded as an accident.

Some of what lingers is the exclusion for suicide in life insurance payouts. Nationally, Humphrey quotes that the exclusion can’t exist for more than two years, or more than a year in Colorado. The dynamics are that the life insurance providers don’t want people buying a policy and then dying by suicide to leave money to others. If someone dies by suicide in that window, their premiums are refunded. Problems still exist to get proper recording on a death certificate.

The other point that Humphrey makes – which Postmortem contradicts – is that the family must consent to an autopsy. The property rights of a person to their body terminate at death. While family wishes are generally respected with regards to an autopsy, they are unlikely to prohibit an autopsy even if they object. All that must exist is a suspicion of foul play – which is an incredibly low standard.

Keeping It Secret

Humphrey acknowledges that some will desire to obscure the mode of death (suicide) for reasons of their own. His recommendation is that a suicide should not be covered up, but that silence and discretion can and possibly should be used. The challenge here is that covering up any aspect of a death is risky. Doing so risks discovery and the loss of credibility. That can lead to problems that aren’t good for anyone.

There are, in most states, limitations about who can get death certificates and how much information they can get from them. It’s reasonable to record the death as a suicide and have not very many people know that. Few people see death certificates. More frequently, people learn of a death through the obituary, in which anything the family desires can be written. An associate of mine confided that her father’s death was suicide, but the obituary said, “hunting accident.” She wondered who would believe that story when his death occurred in July (not any recognized hunting season).

While I discourage the decision for suicide in all circumstances, there is some perspective to be gained by considering the Final Exit.

[I’ve intentionally omitted the means and methods with their efficacies and problems from this review. My point was to investigate the issues surrounding planned death, not to select a means – or encourage others to do so.]