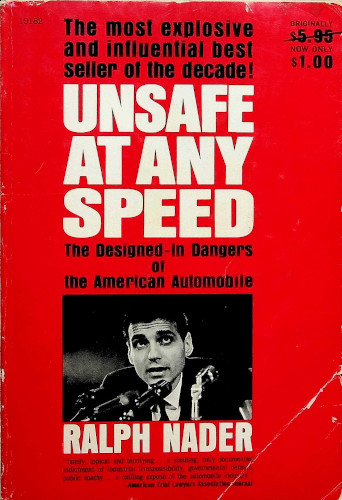

Unsafe at Any Speed

I don’t have a particular passion for automobiles. That’s not why I picked up Unsafe at Any Speed. Ralph Nader may not have been successful in his presidential bids, but what he did do is disrupt industries that were harming consumers. He’s lauded for creating the change in the automobile industry that caused a shift from accidents and outcomes being “all because of the nut behind the wheel” and moving towards building safety into automobiles. I wanted to understand how – not because the automobile industry needed disrupted again, but because of something else equally important.

Craig Bryan uses the analogy between automobile accidents and suicide in Rethinking Suicide. We can’t prevent accidents. There’s no way to know which individual will or won’t be in an accident. However, we can make accidents safer when they happen. Though Bryan doesn’t explicitly mention Unsafe at Any Speed in his work, I recognized that the parallels might go deeper than the analogy as he shared it. As I suspected, there’s more to learn than just how to design cars.

Prevention

“But the true mark of a humane society must be what it does about prevention of accident injuries, not the cleaning up of them afterwards.” Even in the preface, Nader begins the assault on the prevailing perspective of tolerating the trauma created by accidents. Instead of looking for every opportunity to prevent and to protect, the automobile industry looked for ways to deflect blame from the balance of practices that prioritized style over safety.

The tragedies revealed by Unsafe at Any Speed explain that many – though not all – automobile accidents were the result of poor designs that left the vehicles uncontrollable after minor and common disturbances. Imagine if every time you went to turn left or right you were fighting against the car’s attempt to turn too far. Imagine what it would take to counter the forces that wanted to roll a car over because a wheel rim caught the roadway instead of the tires. The Corvair drivers of the 1950s didn’t have to imagine; they had to develop high degrees of driving skill simply to keep the car from creating an accident.

What we needed were different approaches and designs that prioritized a human’s ability to prevent accidents by reducing workload, decreasing critical conditions, and making the car more responsive to driver controls.

Human Factors

Aviation had already solved many of the problems that automobile drivers had to face. Shiny surfaces that caused windshield glare had been eliminated. Controls and gauges were standardized. The information being conveyed to a pilot, while seemingly overwhelming at first, were carefully designed to reduce errors and ensure that the pilot was able to quickly determine a situation. In fact, even private pilots are taught unusual attitude recovery where they must quickly assess an aircraft’s orientation and take immediate corrective actions. It’s not the training that’s important here – its that the whole system is designed to allow the pilot to safely control the aircraft.

When it comes to human factors in automobile design, “They did not forget the driver; they ignored him.” In other words, the lack of human factors work was intentional. They wanted to not be bothered with that troublesome driver who caused all the accidents with their beautiful machine. If it weren’t for the driver, there would be no accidents. They are, of course, right on one level: if no one used their machines, they’d never end up in an accident – or do anything useful, either.

Controls

While the industry was admonishing the driver, telling them to “never take your eye off the road,” they continued to change configurations of controls that made it impossible for a driver to determine by feel which control they had their hand on. They’d tell you never to take your eye off the road, and then require that you do to operate the controls in the car.

The tragedy is that, while making it impossible to follow the advice, they’d blame the driver when accidents would happen, because they were looking at the controls to figure out how to make a change. However, the most challenging problem with controls wasn’t the radio, wiper, or other accessory. The most challenging problem was the automatic transmission.

PRNDL

It’s been years since manual transmissions were common. “Three on the tree” indicated that the shifter was on the steering column. “Four on the floor” was an indication that the manual shifter was on the floorboard. Despite their differences, the manual shifter patterns were notably consistent. Even today, I could hop in a car with a manual transmission and know how to get it into reverse.

The same couldn’t be said for automatic transmission shifters. There was no standard. There are two problems with this. The first problem is that consistency reduces errors. The second is related to the ordering of the shift locations themselves. Numerous needless accidents were reported because people expected they were in reverse but were in drive – or vice-versa. People were being harmed. The solution was simple. Put a non-drive space between forward (drive) and reverse. However, General Motors was having none of it. They already had a pattern they preferred and weren’t going to bow to anyone telling them how to change their shifter.

The pattern they adopted, which was Park, Neutral, Reverse, Drive, and Low, put the reverse and drive adjacent. This pattern was linked to accidents, but rather than voluntarily agree to a better pattern, they resisted – until the government stepped in and made it mandatory.

Maintaining the Illusion

The auto industry was adept at “voluntarily” adopting standards when threatened with legislation. They’d announce their desire to continue to enhance the safety of the general public while narrowly avoiding the government mandate. Sometimes, the government would back down – and the industry would back away from their promises. They’d introduce a safety feature – as standard equipment – during a year of pressure and then drop those features from the next model year.

It was all a part of the carefully cultivated illusion that the cars were safe and well-engineered – without the need for government oversight.

Excellence of Automotive Engineering

The real problem is that the public doesn’t have the knowledge to know when something is or isn’t well engineered. It’s not a specialized skill that they’ve developed. Remember that the Nazis convinced a complacent German people that Jews (as well as Russians and others) were inferior. It was wrong. However, the message was sent so relentlessly that the German people learned to believe something that is so transparently false. So, too, were the claims of the automotive industry that they were following best practices engineering. The public was kept far away from the truth. In April 1963, the journal of the National Society of Professional Engineers opened an article with “It would be hard to imagine anything on such a large scale that seems quite as badly engineered as the American automobile. It is, in fact, probably a classic example of what engineering should not be.”

The illusion of excellence in engineering was seemingly more valuable than the actual engineering quality. We’d come to find out that the industry’s lauded safety and engineering initiatives didn’t produce much, and when it did, it was either not implemented or sold as a luxury.

Safety as a Luxury

Chrysler’s industry-leading safety engineer, Roy Haeusler, admitted that vehicles could be safer without increasing costs if only the engineering is done right in the first place. Said differently, the industry’s primary push-back against enhancing safety was without merit. It was possible to build safer vehicles, they were just choosing not to.

Sure, as a technical matter, a seatbelt would cost a little more than not having one – but not in a material way. Other design changes, like removing the hood ornaments that impaled pedestrians and retooling the dashboards so that they didn’t cause substantial injury to the passengers, cost nothing on a per-unit basis. They just required that the auto industry was concerned about its consumers. They’d provide safety – but only if you paid for it. They cared about your money, not your safety.

Seatbelts that Cause Head Injury

The argument against seatbelts reached comic proportions. When harnesses and safety belts were introduced, racing drivers were criticized for using them – they were told that they lacked courage. Certainly, the public was aware of this – they may have been the ones who were, in part, criticizing the drivers. Today, with decades of racing research on survivability, seatbelts and harnesses aren’t optional. Dozens of innovations have helped racecar drivers walk away from horrendous crashes that would have been lethal just a few decades ago – including folks I call friends.

The non-economic argument against seatbelts was that if passengers weren’t thrown from the vehicles, they might be more harmed by impacting the dashboard. So rather than resolving the secondary impacts, the public was being sold on the idea that being thrown from the vehicle was safer. While this seems ludicrous on the surface, it was one of the things that was said sufficiently it began to be believed.

More than that, by 1958, the automobile industry had the technology to make airbags and install them in vehicles, dramatically addressing their own concerns. It would be the 1970s before cars began to come equipped with them and not until 1998 that they became required. In other words, it took 40 years for life-saving technology to be standard equipment – and then only after federal mandate. While Nader helped make progress, he didn’t fully eradicate the problems with the industry.

Which Came First, the Demand or the Offer

The argument that allowed for safety to be a luxury rather than standard equipment was that people weren’t paying for it, so obviously it didn’t need to be a standard feature. The problems with this argument are many, but two key issues are expectation and awareness.

First, the public had been sold on the idea that cars were well engineered and safe – to acknowledge anything else meant that the carefully crafted illusion would fail. That’s not something that the industry wanted. The second issue is that dealers were often not aware of the additional features or their importance and thus car buyers weren’t sold on the add-on safety features.

The result was low demand. That would be excusable if, at the same time, the auto industry wasn’t bundling in useless styling features that consumers couldn’t remove. They had to have features that added to the allure but provided no protection. It wasn’t that the industry ignored the need for safety, they worked against it, because acknowledging it would hurt sales.

Wish Fulfillment

The auto industry in America had a problem. The problem was that they wanted to produce cars at a rate greater than the actual need of the consumer. If the car had a five-year lifespan, they wanted the consumers buying a new car every three years – or, ideally, every year. To get them back in the show room, they had to sell more than features, because there weren’t that many new features. They had to sell people on a lifestyle, on fulfilling their wishes to be different people than they were. Somehow cars had to make you more fun, smarter, and every other desirable attribute that a consumer could think of.

The trend towards selling wish fulfillment didn’t stop with automobiles. Vance Packard in The Hidden Persuaders explains how marketing began to overtake us, how we stopped buying products and started buying happiness. However, this was in stark contrast to the admonishment we’d receive once we had purchased the vehicle.

Enforcement, Education, and Engineering

In 1924 and 1926, two traffic safety conferences were convened by Herbert Hoover, then Secretary of Commerce. At these conferences, the resonating message was “The Three E’s.” Enforcement, education, and engineering would safeguard the public from the hazards of automobile accidents. Engineering meant highway engineering – not automobile engineering, which we’ve already discussed wouldn’t even meet the bar of sub-par. Enforcement and education were carrying the heavy load, and they were heaped on the backs of the motorist.

The problem is that enforcement didn’t work. According to Unsafe at Any Speed, “In Connecticut, during Governor Ribicoff’s well-known crackdown on speeders, the number of accidents and injuries increased and so did the injury rate per vehicle miles traveled.” Similarly, in the article, “The Effects of Enforcement on Traffic Behavior,” Dr. Michaels concluded that the different amounts of highway police patrol showed no reliable difference in the number of accidents on the roads. In short, enforcement didn’t work – even if it did make drivers occasionally feel like criminals.

Education, then, should carry the heavy burden. They’d teach drivers to drive carefully. They’d be sold with scare and shame tactics to improve their driving. We’ve already explained how human factors often put safe driving outside of the reach of the normal driver. Our more recent experiences with scare tactic programs illustrate how ineffective these approaches are. The US Surgeon General declared Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) a potentially harmful treatment approach for substance use disorder (SUD). Its fear-based approach didn’t, doesn’t, and never will work. (See Chasing the Scream, The Globalization of Addiction, and Dreamland for more on SUD.)

Failure to Stop

The citation is called “Failure to stop.” It’s given to the driver. The presumption is that if a driver failed to stop when appropriately signaled by a sign or traffic light, it must be their fault. A failure of the braking system isn’t often considered. If they overrun the distance, they were speeding or failed to react quickly enough. If they don’t appear to slow at all, they must have failed to apply the brakes.

Even in the event of a failure of the breaking system, the driver is often still blamed for a failure to properly maintain the vehicle. Even for vehicles built in the early 2000s, sometimes, brake lines were constructed of oxidizing (that is, capable of rusting) materials. The result is often a catastrophic failure of the line and resulting loss of brake efficacy. For me, this isn’t a hypothetical example. A 2002 Chevy Suburban that we owned suffered a failure of brake lines during a long-distance trip. Of course, the replacement lines that you paid to have installed were a stainless steel that wouldn’t rust.

There are two important components here. First, why would manufacturers use materials that could oxidize on the bottom of the car, which is in contact with salt and road spray, in a critical system? Second, how could a consumer know that their brake lines were compromised before the critical failure? The answers are unknown but troubling.

In the end, the law recognizes the driver as the agent. (See The Mind Club for more on agency.) They’re to blame for a failure to stop whether the design of the car itself was or wasn’t a significant contributing factor.

Where Rubber Meets the Road

The problems for the auto industry didn’t end at the end of the manufacturing line. Cars left the line dangerously overloaded. The tires on the vehicles weren’t rated to carry the amount of weight when the passengers and useful capacity of the car was considered. They would roll off the line with no one in them, but when fully loaded with passengers and luggage, they often exceeded the tire ratings.

That’s the tires’ official ratings. The industry wasn’t regulated or self-controlled to a degree where there was consistency in testing and marketing of tires in a way that a consumer could recognize the problems with their new car or purchase new tires when they needed to. The options were too complex, opaque, and inconsistent for the consumer to be successful in getting the tires they needed.

Today

Today, things are different – but, as noted, not perfect. What’s terrifying is how many other industries are working in their self interest rather than working towards the kinds of standards, control, and consideration for humans that leaves the world better.

As I ponder suicide and the programs that operate without either a theory of action or any scientific basis, I wonder how many other ways that we proceed blindly accepting what we’re told rather than recognizing that we’ve been sold a lie. I’m beginning to wonder how many of our programs and advances are Unsafe at Any Speed.