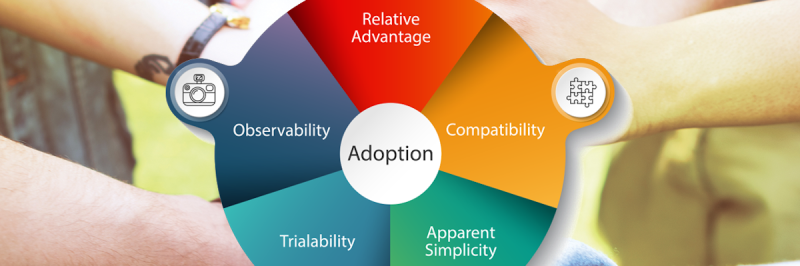

What makes some changes successful and others unsuccessful? In the end, it’s almost always the degree to which the people adopt the change that is being proposed. Everett Rogers knew that only those farming innovations that were adopted mattered, and that’s why he looked for the factors that influence adoption. In the end, he discovered just five things that drive adoption – or not.

The Five

The five factors from Roger’s original work are relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability. Of these, only one of the factors is negatively oriented. To make all the factors all positively oriented, we’ll invert complexity and call it “simplicity.”

Relative Advantage

When we start a change project, we start with an expected value to the organization, but we often fail to translate that into the advantage for the individuals who we’re asking to make the change. The more we’re able to make someone desire the change for their own benefit, the more likely it is that they’ll adopt the change.

Compatibility

The counter-intuitive changes that we try to make are some of the hardest, because they’re inherently incompatible with the existing way of doing things. Anything, even those things that aren’t counter-intuitive, that isn’t compatible with the existing approaches are difficult. If it’s “always been done that way,” then you want to make the change as compatible as possible.

Apparent Simplicity

Complexity prevents adoption. As change specialists, our goal is to make the changes we’re asking for simple and straightforward. The reason that training and education is so effective for change is because it takes the complicated and makes it apparently simple – or at least doable.

Trialability

Change managers resist giving people the option to go back to the existing ways of doing things, but it may be the right short-term answer. Where possible, giving people opportunities to try the new approach in a safe way – and go back to older approaches – will increase adoption. Certainly, there’s a time when going back to old ways is no longer acceptable, but there needs to be a period of time when trying is okay.

We see this factor playing out in the trials for services of all types. Products have return windows. Services have free trials for a period of time – and even discounted rates for a longer period.

Observability

We need a bit of social contagion to take hold to help us get the word out. As Rogers noted in Knowledge-Attitude-Practices, we need to know that people we know are doing it to change our attitudes. By creating natural and consistent ways of making the desired behavior observable, we let others know that it’s safe to proceed with the change, because others are showing success with it.

If you’ve ever wondered why there are so many “like” and “share” buttons on offerings of all kinds, you now know why. Even in the cornfields of Iowa, where Rogers did his research, letting others know what you were doing mattered. Maybe the next time you’re driving down the road, you’ll notice the signs at the end of the road indicating what kind of seeds the farmer is using – a simple way to create observability in a low-tech world.

Resources

- Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations

- Rogers’ Adoption Curve change model

- Rogers’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices change model