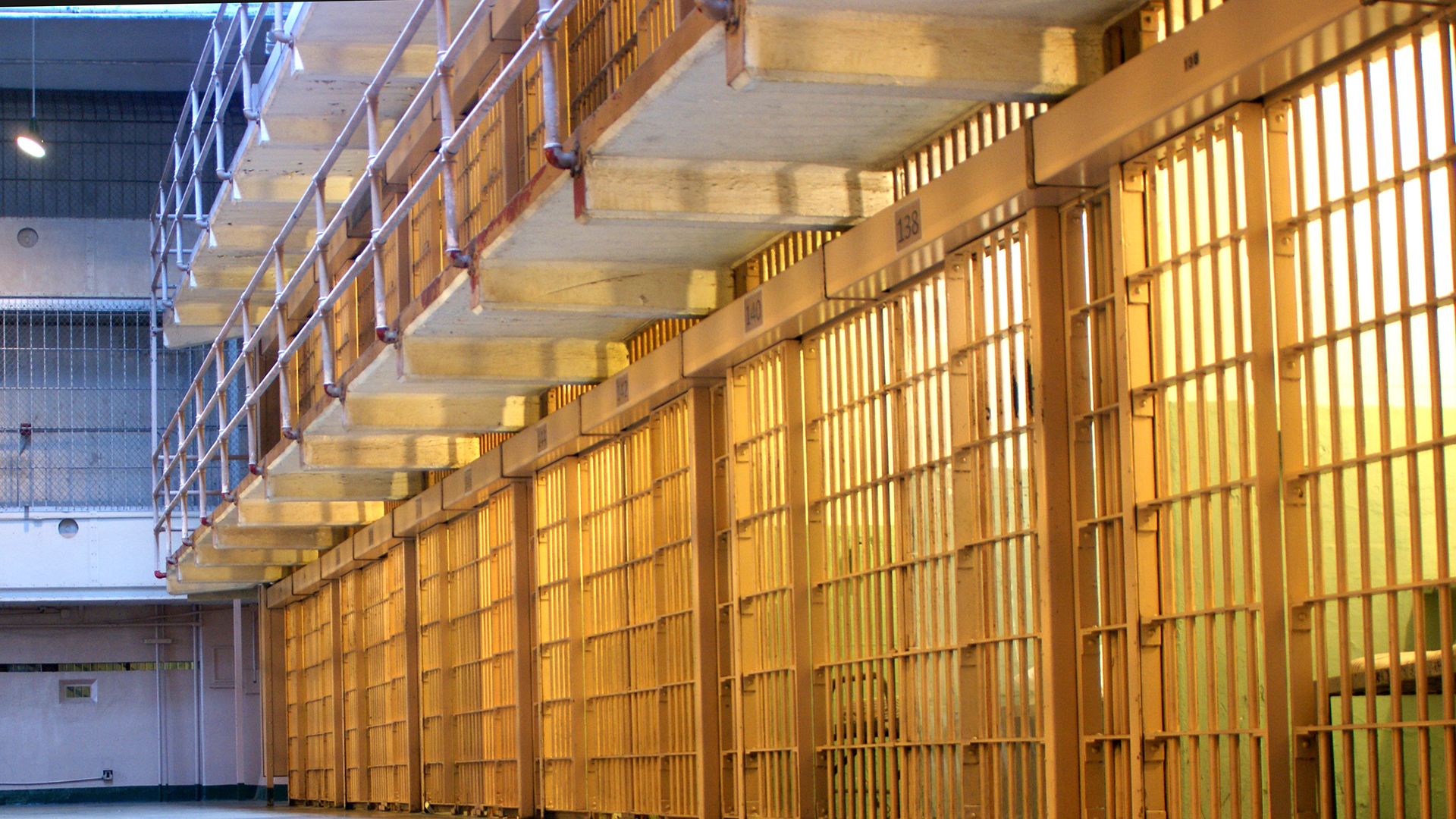

Prison Psychology

It may not seem like there are many choices when you’re a prisoner, so there shouldn’t be much to learn about change, but there’s more to prison psychology than meets the eye. What we know about how easily things devolve started in a basement on the Stanford campus in August of 1971.

Power Corrupts

It was a simulation experiment to see what happens when there’s a perception of power. It was set up by Phillip Zimbardo, and it involved a group of participants randomly split into prisoners and jailers. The simulation was due to run for two weeks but was aborted after there were concerns for the psychological and physical safety of the participants.

In short, the experiment had jailers becoming progressively more aggressive and prisoners becoming progressively more subversive. Christina Maslach, Zimbardo’s then-girlfriend and now-wife, persuaded Zimbardo to halt the experiment due to these concerns. The conclusion that has been taken from the experiment is that power, left uncontrolled, will cause people to behave inhumanely to other humans. Despite the criticisms of the experiment, there’s still widespread belief that power corrupts. (See The Lucifer Effect for more on the experiment.)

Inhumane

It was the research of Albert Bandura that may have shone light on the root cause for the Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE), which may be our ability to disengage our morals. Bandura’s book, Moral Disengagement, is a guidebook for how to create situations where good people will violate their moral code. From majorities and authorities to breaking tasks apart, it explains how some things confuse our moral compass and why we should design solutions to avoid these things. (See the post, The Necessity of Neurology, for more on majorities and authorities.)

When any group of people is identified as being non-human, the rules of humanity and morality break down. As a result, the first step to breaking down the moral moorings is to make people no longer people but instead animals – or, better yet, vermin, as was done in the SPE.

Respecting Change

For change managers, this means clear guidance to ensure that even the most vehement detractor remains human and therefore subject to the same respect that every human deserves by nature of being human. This can be difficult in the heat of disagreements about change, where logical fallacies creep in and name-calling seems to become the norm. (See Mastering Logical Fallacies for more.)

The best run prisons are ones where the jailers and the prisoners respect each other and recognize the humanity of the other group. The prisoners realize that the jailers are doing their job, and the jailers recognize the prisoners as humans who have made a mistake rather than non-human animals.

The Prison of Status Quo

Too many change managers feel like they’ve been jailed by the status quo. It resists the changes that the change manager feels are critical to the organization’s survival. For change managers to accomplish their mission, they cannot attempt to overpower or dehumanize the status quo. It’s formed by people who are trying to do their best and do something that has worked for everyone.

By building relationships that recognize the value that the status quo brings – even if it must be changed – it’s possible to build relationships with everyone in the organization and make them allies on the journey of change instead of devolving into mudslinging and resistance.