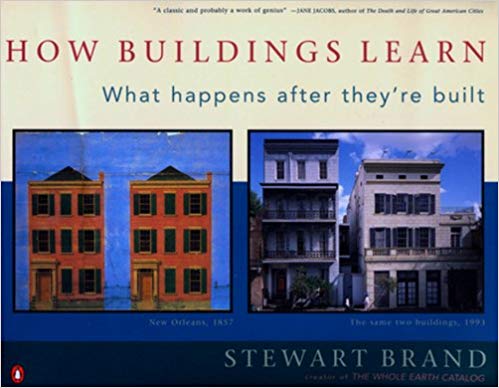

How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built

I’m not an architect, but as an information architect, I’m curious about how classical architects approach the problems of buildings that people love. This journey led me to Stewart Brand’s book, How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built. I was first introduced to the book back in 2011 while reading Pervasive Information Architecture. It surfaced again in Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s book, Antifragile, and in Peter Morville’s Intertwingled. In every case, the reference is to how buildings change (or, in Brand’s language, “learn”) over time.

In information architecture, we’re faced with a rate of change that Brand and his colleagues couldn’t comprehend. While the idea of buildings being torn down in a few decades was alarming to the architects, as information architects, we don’t expect that our architecture will last a decade. The rate of change is too high.

Buildings Shape Us and We Shape Them

Winston Churchill famously said, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” This is a simplification. In truth, after we have built a building, it shapes the way we interact with one another, and then we revise it to fit our new needs. It then further shapes us, and we repeat the process of adapting it.

The biological point of view is that of ecopoiesis – that is, how an ecosystem is formed. There’s some starting event (building a building for instance) and then continuous co-evolution of the organisms (humans) and the environment (building). It’s true that we shape our buildings and then they shape us – and vice versa.

However, like any ecosystem, the rate of change and adaptation isn’t even across the entire system. Some parts of the system change quickly, and other parts of the system move more slowly. It’s these sheering layers that make changes in buildings so interesting.

Sheering Layers

Brand built on Frank Duffy’s work and solidified a model for different layers of the building that operate at different speeds. Look at the diagram from the book:

Here, the layers are all represented. The idea is that the site is permanent (at least as permanent of tectonic plate movement). The stuff in the inner layer is ephemeral. The changes in the stuff is very rapid compared to the rest of the building. Let’s look at each layer:

- Site – Permanent.

- Structure – The most persistent part of the building. The lifespan of structure can be measured in decades to centuries. When the structure changes, the building has changed.

- Skin – The façade or outer face of the building is expected to go out of style and to be replaced every 20 years or so to keep up with fashion or technology.

- Services – These are things like HVAC, elevators, etc., which simply wear out over the period of seven to fifteen years.

- Space Plan – Commercial buildings may change occupancy every three years or so, driving a change in the way internal space is allocated. Domestic homes in the US are, on average, owned for 8 years.

- Stuff – These furnishings and flairs change with the seasons and the current trends.

The rates of change for different layers occurring at different times creates sheering forces, where the slower-moving layers constrain the faster-moving layers. The stuff can only change and grow so much before the space plan gives way and, ultimately, before the structure itself would need to change. Anyone who has watched a reality television show on hoarders knows that their propensity to acquire stuff is limited by the space they have.

Different Types of Architecture

It turns out that, while all buildings share the same basic layers, there are categories of buildings that operate very differently. Commercial buildings are subject to market pressure and frequently changing tenants, making them more volatile. Domestic (i.e. residential) buildings have owners for longer periods of time and tend to be adapted with smaller changes rather than wholesale renovations on a periodic basis. Institutional buildings are relatively fixed and permanent, as the structure itself becomes a symbol of the institution. Institutions are often holders of trust, and change is resisted as much as possible. (See Trust: Human Nature and the Reconstitution of Social Order for more.)

The sheering layers vary inside of these different types of buildings. A commercial building might replace the services at their planned end of life, because the outage is more disruptive than can be reasonably tolerated. Domestic buildings often run their services until a complete failure. Institutions behave more like commercial buildings in their replacement of services but almost never replace their skin, thereby more closely modeling domestic buildings.

Problems with Architecture

Brand spends a considerable amount of time discussing what is wrong with architecture and why it’s such a struggle to get good buildings.

Overspecification

The top culprit seems to be overspecification. That is, little is done to ensure that the building is adaptable to the purposes the occupants have once they’re in the building. Buildings are built so that it’s difficult to get wires through walls, making it harder to adapt the latest technology. All buildings are predictions, and all of them are invariably wrong.

Brand breaks these into high-road and low-road buildings. The former are what architects typically build. They’re bright, shiny, expensive, newer, and difficult to change. Low-road buildings, by contrast, are more adaptable. They adjust to meet the needs of their tenants, and their tenants don’t mind adjusting them to fit their needs. These older buildings may not be a perfect fit for anything, but they’re a good enough fit for most things.

Leaky Roofs

Frank Lloyd Wright may be the greatest American architect of all time, but I don’t want one of his buildings; all his roofs leak. He, in fact, quipped that it is how one knows it is a roof. By the 1980s, eighty percent of all post-construction claims were for leaks. During the same time, malpractice for architects was higher than for doctors. It would be tragic if it weren’t preventable.

We know what makes roofs that don’t leak. We know that flat roofs are going to leak – period. We know that, the greater the pitch, the less likely the roof is to leak. We’ve got all the knowledge, but because of the desire for appearance, we sometimes ignore what we know.

Wrong Metrics

What gets you into Architectural Digest isn’t how tenants love a building. What gets you into Architectural Digest are the pictures taken before people are in the building. It’s all about the design and none about the use. While some progress is being made in getting better metrics that measure – *gasp* – what occupants think, the progress is painfully slow.

If your measure is on pictures that have no relationship (or very little) to reality, it’s no wonder that occupants of the building aren’t happy. Architects aren’t motivated to make the actual users happy with the building they get.

Poor Learning

Brand admits most of the architects he knows are hustling just to survive. That makes it difficult (if not impossible) for them to invest the right amount of energy learning about the latest materials, techniques, and ideas for improving their trade. While there are standards for continuing education now, Brand seems concerned that these aren’t sufficient when architects are under such constant pressure to produce just to survive.

What’s Love?

Still, some architects buck the trends and create buildings that people love – real people who really occupy them. Those architects, as they age, have found ways to create buildings that not only fit the occupants from the start but also adapt gracefully over time. This is a rare condition. My first highlight in the book is “Almost no buildings adapt well.” Adaptability and age seem to be the key ingredients to get people to love a building.

Hire an Architect

Brand is clear that the power in building buildings doesn’t reside with the architects. While they’ll be called in for a few showplace buildings, the developers do most of the action. They may consult an architect at some point, but the architect rarely runs the show.

Because architects are often relegated to a small percentage of buildings where art is more important than functionality, the industry has become stuck. Most people don’t believe that architects are required, because the results they get when using an architect don’t seem to justify the expense.

Habitat, Property, Community

Buildings need to be three things at the same time. They’re a habitat for their occupants. They’re the property. At the same time, they’re also a part of the community. Buildings must fit their occupants and the place they’re in. They must sit on the site that they’re built on (with rare exceptions). Buildings aren’t one thing. They themselves are a sheering layer between the wants and desires of the occupants and the desires of the community.

Markets, Money, and Water

There are three things that change buildings: markets, money, and water. If the market changes and the location (site) is no longer desirable, then changes will need to be made to the building to keep it acceptably interesting to potential occupants. Markets can cause buildings to be built and torn down in rapid succession. (Consider the churn of casinos in Las Vegas as an example.)

Money can mean radical changes to the building. A lack of money can stagnate change or send the building into an inevitable death spiral of maintenance and repair that, in turn, sends occupants scurrying for a new place.

Water is the great destroyer of buildings. David Owen said, “Houses seem to deteriorate from the bathrooms out.” It makes sense. Bathrooms are the place where there is the most water inside of a home, and, too frequently, the water isn’t vented outside. Most homes are built of wood and other materials that don’t do well with prolonged exposure to moisture. Mold grows in the presence of heat and moisture. Homes are designed to be warm enough for their human occupants, and bathrooms are nearly constantly moist.

Not all the changes brought on by markets, money, or, particularly, water are appreciated.

Vernacular

It’s what they say. Vernacular is the native language of a region. When it comes to building, it’s the native way that people build. The way that homes are built in the North and the way that they’re built in the South are different. They’re built different in the extreme temperatures of the East Coast from the houses in the relatively stable temperatures of the West Coast.

There’s not one right way to build a house or a building. However, there are ways that are more suited to the materials available in the region and the techniques that are effective in the climate. Architects do well to understand the region that their creations are going in, so they can mimic the best practices of the region.

Oversize Your Components

The best advice that Brand has is to oversize your components – he expresses this in every way, including the structure. You want to oversize the carrying capacity of the structure, so that new floors can be added. Before computers were available to optimize everything, builders added more capacity to ensure that everything would just work. Oversizing components creates a “loose fit.” That is, the occupants can decide later to adapt the building. As was mentioned above, overspecification is one of Brand’s key concerns.

Open Offices

Before ending, it’s important to note that Brand spends a bit of time speaking of the fallacy of open offices. He explains that people want acoustic privacy but visual transparency. He explains that the initial experiments with open offices didn’t exactly succeed, but that didn’t stop the fad from catching on – much to the dismay of managers.

I’ve run across the open office idea numerous times in my career, particularly as I’m coaching clients on how to be more collaborative or innovative. They can’t seem to let go of the idea that they want a more open, collaborative space – until they’ve done it once. Everywhere you look, you’ll find evidence that it doesn’t work… but only if you’re willing to look.

For instance, in Creativity, Inc., Ed Catmull explains the genius behind the Pixar buildings and how they encourage interactivity. At first glance, the open concept is in. However, on deeper reading, you realize that Jobs made a common space where people could go to. It was a space that needed to be crossed for them to get to their private spaces.

Sometimes you just can’t stop a fad with facts, experience, or rationality.

Information Architecture

I read How Buildings Learn to stabilize my understanding of information architecture and learn from building architecture. The few key takeaways that I already knew but was reminded of are:

- Vernacular – Build to the environment you’re in. In information architecture this means using terms that are familiar and approaches that work well with the users.

- Plan for Change – Buildings get bad marks for their adaptability. Information architectures fail if they’re not hospitable to change.

- Change Sheers – Change doesn’t happen at the same rate. There are parts of the system that should be designed to change slowly and others to change much more rapidly.

- Oversize Your Components – While all predictions are wrong, predicting that things will grow is a safe bet. When you’re considering whether to put something in up front to be prepared… do it.

Whether you’re building an information architecture, a real building, or neither, I’m pretty sure you’ll learn something important from How Buildings Learn.