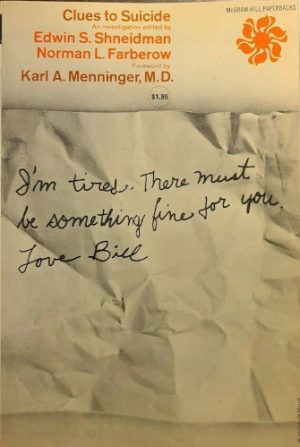

Clues to Suicide

If I presented you with a selection of genuine suicide notes and a set of manufactured suicide notes from a matched set of individuals, would you be able to tell the difference? This is at the heart of Clues to Suicide. Edward Shneidman famously got interested in suicide by stumbling across suicide notes. (See Definition of Suicide.) He and Norman Farberow started the Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Center and edited Clues to Suicide in 1957. It’s a part of an initial set of research and writing to start the modern period of suicide research.

Mortality

Even in the 1950s, it was clear that suicide was more prevalent than murder – but that the public didn’t know that. Even today, mass shootings are far more newsworthy than suicides. We focus on gun violence as if it’s only murder.

Real or Imagined Loss

The fluid vulnerability theory of suicide (developed decades after this book was published) explains that people have a baseline risk for suicide, and then are driven by triggering events into a different stratum of risk. (See Brief Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention.) Often, that trigger can be classified as a risk. Sometimes, the risk is a relationship, and sometimes the loss is a sense of safety. Clues to Suicide makes the important point that the loss that triggers ideation about suicide need not be real. It can be either real or imagined.

Consistent with Sapolsky’s work in Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, we as humans have the capacity to predict the future. That allows us to experience stress that hasn’t happened. Instead of being confined to immediate threats to our survival, we can predict a loss of job or a loss of love and experience a stress response immediately. The problem is that our predictions are notoriously bad. (See Superforecasting and The Signal and the Noise.) This is particularly true of our happiness, as Gilbert explains in Stumbling on Happiness.

Less Trouble to Everyone Concerned

Sometimes, people believe that they’re a burden; consistent with Joiner’s Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of suicide, burdensomeness is a predictor of eventual suicide. To be clear, there are probably two different modalities of suicide. One is planned and the other impulsive. In both cases, the cognitive processing may consider the degree to which someone is a burden to others.

The challenging aspect of this burdensomeness is that it’s measured from the perspective of the person and may or may not reflect the actual degree to which others perceive them as a burden. However, in some cases, the concept of burdensomeness shows up as a desire to minimize the amount of pain those left behind will feel. As a result, they may choose to attempt suicide in a way that they believe will be the least painful for those they leave behind.

Of course, most of this is fallacy, because the loss will be immense when someone dies by suicide, and people rarely perceive their burdensomeness to others equitably.

Socioeconomic Status and Suicide

Even in these early times, it was clear that suicide was occurring at higher rates in those who were privileged. Today, we think about this in terms of socioeconomic status (SES). Certainly, suicide occurs in all levels of SES, but there seems to be an odd concentration of suicides at higher levels.

As I’ve suggested in previous reviews, this may be due to maximization and/or the expectation gap. (See The Noonday Demon.) When people constantly have higher expectations than are possible, they are necessarily disappointed. This disappointment can lead to burnout. (See ExtinguishBurnout.com) Sometimes this disappointment doesn’t find an outlet or develops into hopelessness, and suicide seems like a good solution. (See The Psychology of Hope for more about how hope is built, and The Hope Circuit for more about its impact.)

Many of the threads that research has followed for decades are laid out in Clues to Suicide. Despite its age, it may be a good place to start to see where we’ve been.