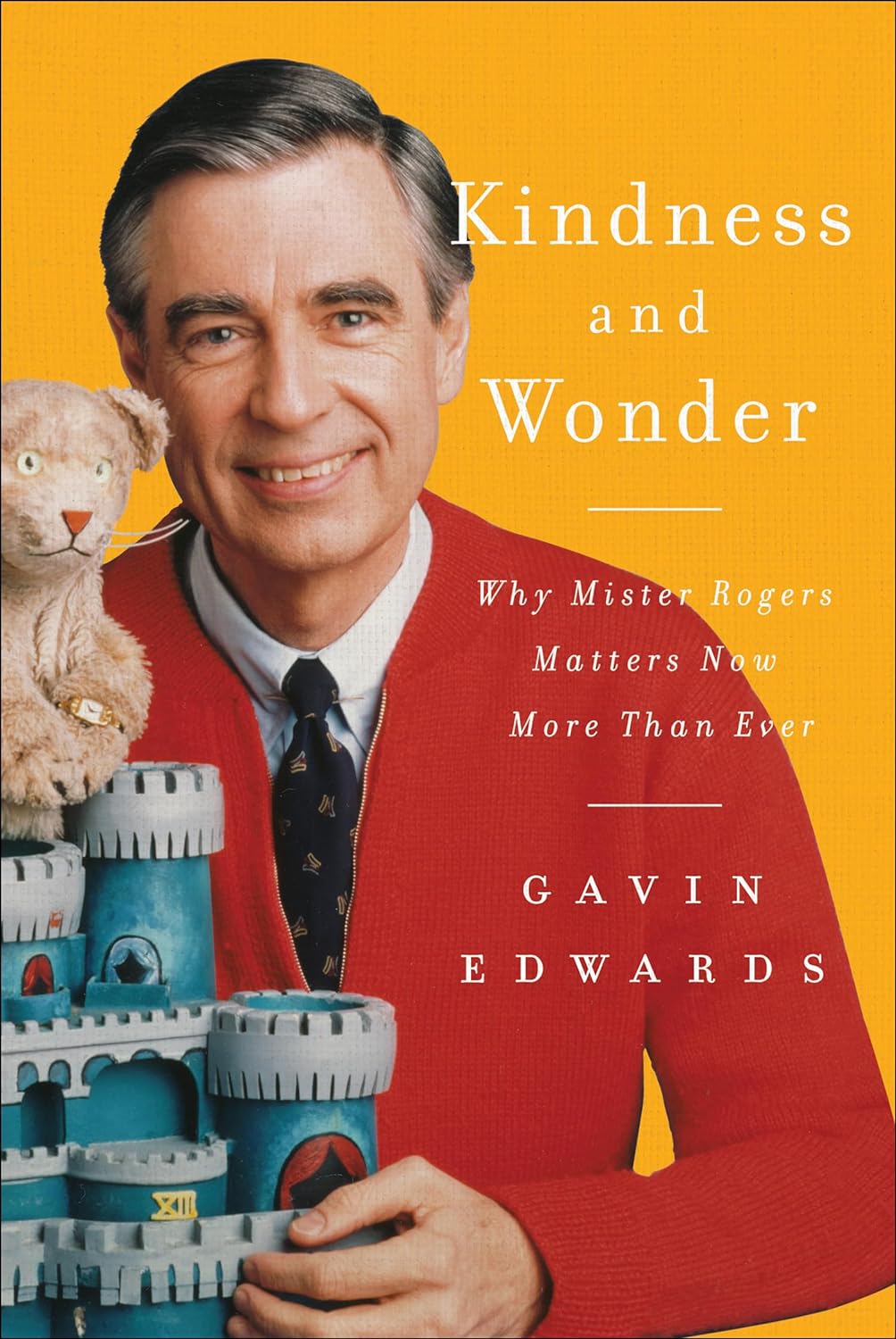

Kindness and Wonder: Why Mister Rogers Matters Now More Than Ever

I recently finished printing a 3D model of Mister Rogers’ neighborhood trolley. It brought me a strange sense of joy to think of the little trolley that transported viewers from the real world of Mister Rogers’ house to the make-believe world. Both ends of the trolley track ended in places of kindness and wonder. Kindness and Wonder: Why Mister Rogers Matters Now More Than Ever is an exploration of how he wove principles and values into the social and emotional education of children.

The Helpers

I mentioned in my review of The Good Neighbor how Rogers’ mother implored him to look for the helpers. He took this to heart and was always scanning the news, sidelines, and behind-the-story story for the helpers. On the surface, this hunt seems like little more than a chance to placate our need for balance. Rick Hansen in Hardwiring Happiness explains how we can – and should – focus on the positive to counteract our natural bias toward negativity.

However, there’s a deeper insight at work here. To see it, we need the lens of Rick Snyder and The Psychology of Hope. He explains that hope is a cognition based on our knowledge of how to reach the desired goal and our commitment to reaching it. Extending this a bit, hope operates on internal and external dimensions. We can know how to do it ourselves – or believe someone else does. We can feel as if we have the strength ourselves or that others will come to our aid.

When we don’t look for the helpers, we don’t find them, and we fall victim to What You See Is All There Is (WYSIATI). (See Thinking, Fast and Slow for more about this bias.) By looking for the helpers, we’re able to call the idea of others helping us in our burdens to mind more easily. That means that we can more easily retain hope.

The Difference One Person Can Make

When speaking of Fred Rogers, one might easily see the difference that one person can make. His seemingly tireless dedication to using television to teach children left the world a better place. However, if you asked Rogers about this phenomenon, he wouldn’t be speaking of himself. He’d be speaking about a friend named Jim.

Jim Stumbaugh was a “big man on campus” who was the star in track, basketball, and football. After sustaining an injury, he ended up in the hospital. Rogers’ mother arranged for Fred to take Jim his homework. Fred and Jim became lifelong friends. Jim’s influence redirected Fred Rogers in ways that likely led him to be the powerful force for good that he became.

It’s important that Jim didn’t do this intentionally. He wasn’t intending to change the world – he was simply returning the favor by helping the “shy kid” learn to be himself more fully. By helping Rogers become himself, he gave the world a great gift.

The question it leads one to wonder is how can a bit of kindness – nothing monumental – make a real difference in the world? And also, how could you ever know how your little acts of kindness will change the world?

The Magical Tiger

Daniel, the striped tiger, was a small puppet provided by the station manager – whose name was Dorthy Daniel. Daniel popped out of a clock with no hands and leapt into the hearts of little viewers and Rogers’ original cohost of The Children’s Corner, Josie Carey (Vicari). Josie, with cameras rolling, admitted to Daniel that she was upset. It was a magical moment when Josie was pouring her heart out to a puppet. Reportedly, Carey would later attempt to recount her discussions with Daniel to Rogers, having forgotten that cameras were rolling and, more importantly, that Daniel was performed by Rogers.

One can’t help but see that if an adult can have a conversation with a puppet, then it’s safe for children to do so as well. By speaking of her feelings to a puppet, Josie modeled the kind of emotional vulnerability and emotional management that Rogers hoped, he would later tell Senator Pastore, children’s programming could bring to America.

Learning by Doing

When Rogers started in television, it was a new medium without rules. It started basically as radio with a picture before evolving to what it is today. During this evolution, people were doing things to see what would and would not work. There was a period of intense experimentation.

When Rogers came to Pittsburgh, he wasn’t just experimenting with how to create a children’s program, he was finding ways to get things done without either financial or people resources. The trademark opening of Mister Rogers Neighborhood was inspired in part by the fact that Rogers wore sneakers on set to eliminate the noise as he ran from one thing to another.

Yes, he did work before airtime, but during airtime, he’d move from playing music on the piano to being the puppeteer, and, by the time he had Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, acting on screen. It’s true that you learn a lot by doing – and everyone on the team was doing a lot. David Newell, for instance, was the shows’ publicist and the actor portraying Mr. McFeely. Joe Negri, a musician of some acclaim who worked on the show, also found himself in front of the camera as Handyman Negri.

Simplify Complicated Things

It’s a subtle skill that isn’t noticed when done right. Taking the complicated and distilling it to its minimal elements makes things that appear complicated simple. Einstein reportedly said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.” Lost Knowledge explains how our schema for understanding topics gets more complex and how this can interfere with our ability to speak to others. The Art of Explanation and The ABCs of How We Learn explain how we need to simplify complicated things to make them easier to learn.

Rogers’ process for simplification was described as a translation to “Freddish.” (See The Good Neighbor for the process.)

Safe Place to Go

When your world is chaos. When your parents are fighting when they’re home. When you wonder where your next meal will come from – if at all. When you don’t know where you’re sleeping for more than a few days at a time. These are the times when you need a refuge. This is – to a greater or lesser degree – what Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was. It was a place where kids could see good in the world, possibilities, and a baseline stability that may have been lacking.

The challenges of poverty aren’t unique to the decades when Fred Rogers was producing the show. Robert Putnam was able to see the differences between the affluent and the less affluent in his book, Our Kids. His earlier book, Bowling Alone, speaks to the breakdown of community and how it harms people who have the least resources. The breakdown of social capital (Putnam’s words for it) has only continued based on the feedback about churches continuing to lose members and attendance.

A Message of Understanding

Not only was the neighborhood safe, but it was a place where understanding and acceptance pervaded. There were the episodes that broke color lines and those that spoke of the difficult topic of divorce at a time when it was unspeakable. Rogers projected this sense that he was listening to each individual child – and was careful not to appear as if he were spying on them through the television.

Understanding is a good start, but it’s not where Rogers stopped. He wanted every child to know that they were accepted as who they are, just as he was accepted unconditionally by his grandfather.

Make Goodness Attractive

One of the difficult challenges facing anyone who wants to do good is to change the perception from the idea that doing good is hard or painful to a place where good seems attractive. Today, we see too many examples of shortcuts and swindling. We hear stories of harm and horror. The journalism adage that “if it bleeds it leads” leads us away from the benefits of goodness.

More than ever, we need to help everyone understand how helping others helps you – not in a tit-for-tat sort of way but rather that you receive while giving. (See The Evolution of Cooperation for more on tit-for-tat.)

Translating Care from Inside to Outside

The Dalai Lama is known the world over for his compassion. However, there’s one place where Fred Rogers might disagree with the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama explains that compassion is having empathy for someone’s suffering and a desire to change it. (See A Force for Good.) Rogers might push this further and seek tangible progress in translating the internal care we have for others into outward signals, signs, and actions.

It’s probably splitting hairs, as the Dalai Lama seeks to project his influence without much direct power – but it’s important to realize that people don’t know about our desire for their care unless we can demonstrate it to them with Kindness and Wonder.