On Second Thought: How Ambivalence Shapes Your Life

“Ambivalence is our constant companion.” It’s my first highlight from On Second Thought: How Ambivalence Shapes Your Life. This isn’t the first work of William Miller that I’ve read. He coauthored Motivational Interviewing and Quantum Change. I’ve learned to trust his insights and recognize that there’s more to the story than we may have thought or been told. I’ve learned that, sometimes, the power comes from the conflicting thoughts that drive ambivalence.

Indifference, Ignorance, and Ambiguity

It’s important to recognize that ambivalence is a conflicted, contradictory, and vacillating feeling between two, mutually exclusive alternatives. It’s not indifference, ignorance, or ambiguity. There’s a real reason to be concerned and an understanding of the situation. Indifference is not caring. Ignorance is not knowing – and ambiguity is not knowing enough. These aren’t the forces that are in operation when ambivalence is present.

When listening to someone, the way that you can detect ambivalence is the word “but.” It signals the contradiction. It says that there’s more than one side to consider.

It’s Good

I picked up On Second Thought to support a writing effort for a journal article with a friend. In that article, we make a key point that, while ambivalence is seen as a bad thing, it’s not. In the lean manufacturing approach, delaying decisions until the last possible moment is seen as a positive and prevents unnecessary waste. There’s so much that we know in decision making about the value of rational reviews – and the awareness that we don’t do it enough. (See Decision Making and Sources of Power.) Miller states that those with greater emotional ambivalence have been found in research to:

- Be better informed

- Read other people’s emotions more accurately

- Be more creative, perceiving unusual associations and possibilities

- Offer fair and balanced evaluations

- Make more accurate judgments

- Be open to new information and alternative perspectives

- Experience greater sexual arousal and desire

- Be less inclined to make impulsive decisions and purchases

The Inner Committee

While we tend to think about our consciousness as one thing, many scholars have a fragmented view. Daniel Kahneman sees that we have a quick System 1, and a slower, systematic, System 2. (See Thinking, Fast and Slow.) Daniel Goleman, in Emotional Intelligence, explains that we have a rational mind and an emotional mind. Jonathan Haidt expands this to explain the relationship in his Elephant-Rider-Path model. (See The Happiness Hypothesis and Switch.)

However, the Internal Family Systems (IFS) model, as described in No Bad Parts, explains that we have different parts of our consciousness. It’s not that we have multiple personalities, but rather we have multiple aspects of our personalities that have been fragmented. Sometimes, we encounter the parts of ourselves that were exiled, and sometimes we encounter their protectors. They likely have different perspectives than the rest of our consciousness.

Another perspective is that of Steven Reiss in Who Am I?, where he explains that there are 16 basic motivators, and those motivators can come in conflict with one another. The idea that we shouldn’t be in conflict with ourselves or that we shouldn’t ever come into conflict is fiction.

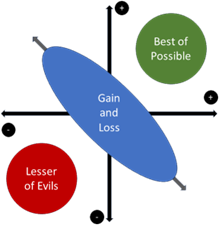

Kinds of Ambivalence

An interesting aspect of ambivalence that isn’t often discussed is how it is shaped by the positives and negatives of the situation. Some situations are choices between two mutually-exclusive, positive options. Others are choosing the lesser of two evils seeking to minimize the pain. The more complicated kind are those with both positives and negatives. A depiction of this follows:

When we’re thinking about ambivalence, we’re more frequently thinking of those in the middle. Consider a job change that requires a move to a new city that you’d like to live in. Here is a table of positives and negatives of the move (which are opposite for keeping the current job).

| Positives | Negatives |

| Better pay, reportedly better hours, an opportunity for career advancement. Greater challenge. | Loss of work friends. Loss of stability and predictability. Will be harder. |

| Get to buy a new house without the existing problems and one that better fits my lifestyle today. | Loss of my favorite features of the existing house, like the garden, the proximity to the market, and safety. |

| Get to live in a city I’ve always wanted to live in. New adventures. | Loss of the community spaces and festivals that I love so much. Need to find new dentist, physician, hair stylist, etc. |

Obviously, the above table is simplified and intentionally devoid of specifics. However, it illustrates that for every positive, there is often some kind of a negative. To gain something, you must give something else up. This is at the heart of ambivalence. The moment the decision is made, the alternative is removed either literally or figuratively. Jack Canfield in The Success Principles says, “99% is a bitch, 100% is a breeze.” That is once the decision is truly made, the alternatives disappear from consciousness.

The Internal-External Conflict

Sometimes, the expectations of society conflict with your expectations of yourself. People with a “stable core” are aware of their beliefs and values and have the courage to stick to them – for the most part. (See Braving the Wilderness for more on the concept of a stable core and Find Your Courage for more on the courage to stick to your convictions.) This may be a requirement to report something incorrect or a requirement to take advantage of other people (in your view). We may be tempted to betray our morals through the temptation of going with what others want – but it often comes with great struggle. (See How Good People Make Tough Choices for moral temptations and Moral Disengagement for how we rationalize it.)

We can see this kind of conflict working both positively – and negatively – in suicide prevention. In the case of bullying and torment, a person’s self-worth (self-esteem) is under attack. Ultimately, this changes the weighting for positives and negatives. Instead of staying alive being associated with happiness and creating good in the world, it’s filled with torment and struggle. If the person’s self-esteem collapses under this weight, suicide seems like a good idea.

Conversely, another person concerned about you can mean that there is hope that the current circumstances are temporary. There’s the chance for things to get better based on your work and the support of others. Instead of the world being an inherently hostile place with no use for you, one can discover the helpful, compassionate responses that are woven into the fabric of humanity. (See Does Altruism Exist?)

In both cases, external forces “put their finger” on the scales of ambivalence and change the chance that a final decision will be made – to leave suicide behind, or, tragically, to take that exit.

The Ambivalence of Authority

Most people don’t like being told what to do. It’s similar to Compelled to Control’s revelation that everyone wants to control but no one wants to be controlled. While not literally and absolutely true, it’s certainly a majority. Occasionally, you find those, like the story of Ralph as told in Work Redesign, who no longer desire autonomy. Their spirit has been broken, and now they’ve resigned themselves to a life that exists beyond their control.

Either Or

One of the limitations of our human minds is that we have a propensity towards binary thinking. That is, we believe that it’s black or it’s white. We ignore the multitude of variations between the two polarities. We see it in cognitive constriction that occurs when we’re under stress. (See Capture.) We see it in the studies of creative thinking under stress. (See Drive.)

One of the best things that we can do to improve decision making is to disrupt this binary, dualistic thinking by introducing a third option. The introduction of the third option opens the possibility to more and reduces the force of direct conflict between the two original options.

Ideal and Actual Self

It was the gap that Carl Rogers was most concerned with. (See A Way of Being for some of his work.) It’s the gap between the internal vision of oneself and the actual self that exists in the world. It’s the same sort of contradiction that Immunity to Change is focused on. How are there discrepancies between intentions and actions? Some of that can be ascribed to the tension between the rider and the elephant in Jonathan Haidt’s model of decision-making. (See The Happiness Hypothesis and Switch for more.) For some, the gap may be the difference between their status orientation and their current status. (See Who Am I? and The Normal Personality.)

When we’re looking at the unmade decisions in our life, we must ask whether they remain undecided because we’re ambivalent about them. We must also consider whether these decisions should remain unmade in their ambivalence – or whether it’s time to make the call. The truth is that, for most situations, there is no space left for the concept of On Second Thought.