Doubt: A History: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson

Doubt is a natural and healthy part of the human experience so when Doubt: A History: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson crossed my path, I was intrigued. What could I learn about doubt?

The great irony of the book is that it is a history of atheism but one that reaffirmed my faith. Doubt is focused on religious doubt but along the way showed a pattern of even the doubters disagreeing with one another. How can I accept that one of the doubters is right about their doubt if the doubters can’t agree with each other about how or why God doesn’t exist?

What is God?

Humans have been trying to make sense of the world around them and the causes for things since we began to walk upright, if not before. (See Man’s Search for Meaning to see Viktor Frankl’s perspective that meaning is the primary drive of life.) We have been seeking a way to better control our lives and our fates through appeal to powerful beings who could intervene on our behalf. The view of what these powers are has varied culturally, from the polytheistic beliefs of the Greeks to the more modern monotheistic belief in one all-powerful God.

Monotheism finds its roots in Judaism. Once God gave Abraham instruction to kill his son, and before he faithfully carried out God’s command, God intervened. Abraham and his wife then filled the planet with their descendants. (Or so the story goes.) This gave rise to Judaism, which in turn gave rise to Christianity. Jesus put a new spin on the old religion, recasting God as a loving father instead of a vengeful and angry God.

Muslims, too, owe their God to the God of the Jews. Mohammad saw himself as the last in a line of prophets, from Moses to Jesus and finally to him. Of course, today we tend to see Islam as a separate religion, but the roots and heritage are the same.

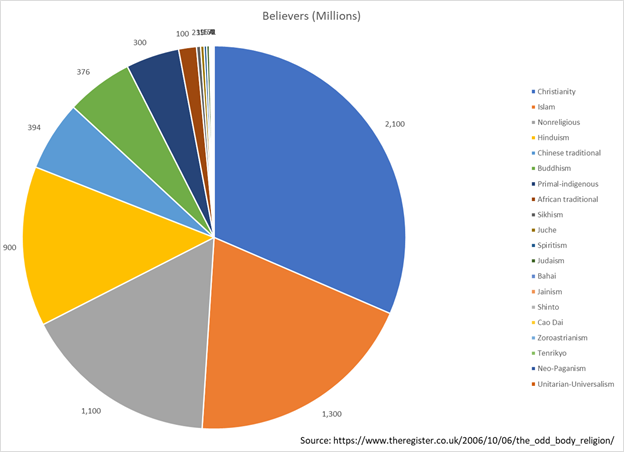

Not all religions can trace their roots to Judaism. Hinduism has a polytheistic approach like the ancient Greeks, with gods having power over different aspects of life. Buddhism doesn’t have a god as such. The approach here is simply to view the next stage in evolution as a higher place, where we’re disconnected from the encumbrances of our lives.

There are as many views of what God is as there are grains of sand on a beach. However, folks generally fall into the preceding handful of categories. See this pie chart of the various religions:

Disbelief “Proofs”

There have been various ideas of God over the eons of our time on Earth, and so too have there been various ideas about why there cannot be a god or why our conception of God must be wrong. A few of the recurring themes in the history of doubt are:

- God is the universe/world – This model doesn’t accept that there is a separate entity called “God,” but rather says that there is a universal force in the universe.

- God logically can’t exist – The proofs offered are different, but they often hinge on the question of who God’s creator is. Since we have no frame of reference for a being that wasn’t created, we assume that this cannot be.

- God is irrelevant – God is unconcerned with the lives of humans, and the presence or lack of presence of a god is irrelevant to our lives.

- God is cruel – Why would someone worship a god who has left the world with so much suffering?

- God was invented to keep people in check – Many of God’s structures seemed be to keep the people in check.

Certainly, there are more variants of the challenges to God’s existence; however, the general idea is that, using our rational thinking and logic, we establish – or fail to establish – a mechanism by which God exists.

Bread and Circuses

The Roman Empire was powerful in its time and strange in its longevity. Some of this is surely due to the times they were in and some to their military presence, but at least some of the reason why the Roman Empire was so successful had to do with how they managed the citizenship. Citizenship was a responsibility. It was something that people could look up to being a part of. (See The Deep Water of Affinity Groups for more on how membership might change perspectives.)

However, the real genius may have been what has been labeled as “bread and circuses.” The bread component is the ability for everyone to meet their basic needs – including, of course, food. This means that, for most, there was enough to eat to sustain themselves. Having your basic necessities met leads to a lower level of angst. It was thousands of years before we discovered how our basic disposition changes when we’re not well fed. (See The One Thing, Willpower, and Predictably Irrational for more on the impact of low blood sugar on decision-making.) Augustus seemed to know empirically that food was a baseline that must be met.

Circuses is a proxy for entertainment. There were grand spectacles that kept people connected to the magic of the empire. They had their basic needs met, and they got regular entertainment. What else could anyone want? It turns out the answer might be fulfillment.

In Drive, Daniel Pink explains what motivates us: autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Richard Florida makes a point that, today, we’re seeing the rise of a creative class, where these motivators are strengthened. However, the drivers have always been there behind the scenes, pulling us towards a different way of motivation. Once our basic needs are met, the next thing we want to do is to meet these higher needs. Strangely, in the times of the Roman Empire, we may have found that folks had a great degree of autonomy and felt a great degree of mastery. The missing component was purpose.

If your life is an endless struggle for survival, and each season seems like the next, you’ll start looking for purpose. (See When – also by Daniel Pink – to understand how we created the concept of time to break the monotony.) We’re hardwired as humans to try to make sense of our surroundings. (See Incognito for more on the way we’re wired to make sense of things.)

Religion is a way to make sense out of our world. It’s a way to ascribe meaning to the things that happen to us, even when some of those meanings are painful for us.

Crime and Punishment

One view of God is that He’s just, and therefore anyone who is suffering deserves it. That is, they’re being punished for something they did – or didn’t – do. This is an awful burden to place upon someone who has fallen victim to misfortune. If you lose a brother, it must be because you did something wrong. If you’re sick, you must not have said your prayers. Or perhaps you had too little faith.

This view of God is inconsistent with the literal meaning contained in the Bible – but that doesn’t matter when you’re unable to read. See Faith, Hope, and Love for more on what these really mean – and why it doesn’t mean that you’ve done wrong.

One view is that God was created to keep those who are less fortunate shrouded in shame. In this way, they can be perpetually kept down. (See Daring Greatly for more on shame and its power.)

Karma and Castes

Transitioning from Christianity to Hinduism, there are signs pointing to the fact that the idea of karma was designed to keep the caste system in place. The caste system places people into different strata in society. The idea is that you have a station in life that you should keep.

Karma holds the system in place by helping to explain that you are responsible for your “lot in life.” That is, you must have done something bad in a past life if you find yourself in a lower caste, or something good if you happen to find yourself in a higher caste. Suddenly, there’s an explanation for your bad – or good – luck in life, and it’s you.

It’s not hard to see how one could hold the position that religion is created by the ruling class to keep the working classes down.

Lenin Read a Book of Marx

Marx, a famous atheist, believed that religion was “the opiate of the masses.” That is, it served to dull the pain of a life of struggle. Instead of being to control, Marx believed it served to mollify people. It’s the answer to what bread and circuses couldn’t do. In a great sense of irony, Marxism took on many of the characteristics of a religion. Instead of a religion that had a god, Marxism had a belief that there was no god and no reason to worship anyone. He began an attack on religion.

Lenin liked Marxism but disagreed about religion being bad. Lenin saw no need to immediately remove religion. It was serving a purpose. In his grand plan, religion wouldn’t be necessary any longer; but until the fruition of the plan, there was little reason to rock the boat. Once peoples’ lives were better, they would no longer need the support of religion.

In a ironic twist, most religions have components of helping out your fellow man. What Marx and Lenin wanted to do was have the community or the state do what most religions said they were supposed to be doing.

Morality and the Afterlife

The start of religion concerned itself only with what was going on in this life. It was some time before the idea of an afterlife came into wide acceptance. Many of the “doubters” were concerned not with whether they believed in a god as most religions defined them, but rather what would happen in the absence of the concept of a god. How would individual power of kings and leaders be limited if there wasn’t a higher authority to which people could appeal their case?

Morality is a tricky topic. Haidt seems to have isolated six foundations of morality, as he describes in The Righteous Mind. Bandura speaks volumes about how morality can be disengaged in Moral Disengagement. Milgram’s experiments showed that, with very tiny nudges, most people – good, decent people – could be encouraged to give what they believed were lethal shocks. (See Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me) and Influencer for more.) It’s no surprise that early philosophers were concerned what would happen if they “killed God” in the service of reason. What happens to morality when you remove its moorings?

With the introduction of an idea that there was something beyond this life, comfort was offered to those losing loved ones, people were more likely to sacrifice themselves for others, and there was a place and time for consequences – both positive and negative – for the decisions made now. The afterlife – or what happens after life – was a good addition to religion, both in terms of easing suffering and in terms of increasing the hold of morality.

The Narrow Gate and the Middle Way

Buddha recommended the Middle Way between self-indulgence and abnegation. Jesus explained, “For the gate is small and the way is narrow that leads to life, and there are few who find it” (Matthew 7:13). For Buddha’s part, he said that it was as narrow as a razor’s edge – one must be vigilant against the seductions of either tendency. Jesus’ call was for others to follow him, and in this call is the complexity of what to do is answered by the question now found on bracelets: “What Would Jesus Do?” – or, simply, WWJD. Both calls are about finding the path where indulgence doesn’t rule, but there’s no self-harm through denial of basic needs.

In many cases, organized religion has attempted to simplify the message to a set of rules that can be followed rather than a set of guiding principles. We know from leadership research into excellence that getting everyone aligned around guiding principles is substantially more effective than legislating every action and thought that every person should have.

Even the army recognizes that no plan survives engagement with the enemy. It may be useful to do the planning exercise, but “commander’s intent” is now included with orders. (See Made to Stick for more on this.) Religion may have run aground on the sandbar of rules instead of being guided by purpose.

Failures of Religion

It doesn’t take a scholar to find where religions have failed us. It doesn’t require much work to find priests and ministers having “inappropriate relationships.” It’s not hard to overhear a Jew and a Catholic having a competition about which religion is better at inflicting shame and guilt on its members. At every level, there are places where religion – as a human institution – has failed. I’ve been too close to churches who have shunned the spiritually wounded. I’ve been in the splash zone as people were shamed for their behaviors and their identity.

It seems pointless to enumerate the failures because they are so many. However, it’s these failures that the doubters latch on to. “If there is a god, how can they let this happen?” is a common cry of both believers and those filled with doubt. It’s a hard question that none of the proposed answers seem to satisfy.

Monopoly on Truth

Doubters – like religions – must have some degree of believing that they’ve got a monopoly on the truth. There’s a belief that you’ve figured it out, and the “others” got it wrong. At one level, this is our ego protecting us and our decisions. (See Change or Die.) However, understanding how we come by our belief that we’ve got the only right answer doesn’t make the consequences any less tragic.

The things that have been done in the name of religion are gruesome. Consider how the Protestants were massacred by a king to prevent a revolt – and how the Catholic Parisians extended the carnage to their fellow townsmen. Here, you have two religious groups who believe that Jesus came to save everyone from their sins. They disagreed with some of the church doctrine layered on Jesus’ teaching, but in most ways, they believed the same things. And in the end, three thousand were dead, because they didn’t believe in the church doctrine.

This is hardly an isolated occurrence in any religion. When we become convinced that we – and only we – know the answers, we become vulnerable to irrational rationalizations about how we’re right and others aren’t. For me, it’s important to realize that we all go through a growth process, from following the ideas of others, to being fluent in our understanding of them, and, finally, to detaching and recognizing that there are other views that should be considered as well. (See Following, Fluent, Detaching in Story Genius for more.)

Successes of Religion

Most of the philanthropy done is done in the name of religion. Certainly, religion harms people, but it gathers people together and rallies them for the common good – and a lot of good is done. Religion connects us to one another and helps us to align to a common set of goals. The pursuit of righteousness with God has shaped the moral fiber of many people. So even in its current imperfect state, the religions of the world seem to serve more than they take away from the experience of life.

Religion also comes with a set of rhythms and rituals that help bind us together. They help us to be better at that trick of mindreading (see Mindreading).

Wanting and Lacking

Among the doubters are those who have found the way. They learned how to not want anything – and therefore not feel as if they’re lacking anything. They realized that a change in their fundamental attitude was “all” it took to change their outlook on life. They realized, rather than comparing themselves to others through material things, that they could look at the world as owing them nothing. They could accept the blessings of the things that they had and not long for more – or different.

When you don’t want anything, then you don’t want for anything. When you don’t feel like you need things, then you don’t lack them. Certainly, there’s a need for basic necessities, but once you’re beyond those, what is it that you lack that you need? The answer is typically nothing.

The Fear of Pain

There’s a power to anticipation. While we may discount future gains when comparing them to current losses, we amplify the potential losses. (See Thinking, Fast and Slow for more on this asymmetry.) This evolutionary trick may have been helpful when the fears could result in death, but today, most of our pains are not fatal. Yet, there are a great many pains that we face that never really happen. They’re imaginations in our mind. They’re projections of stress that may never come to be. (For more on stress, see Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers.)

Mark Twain said, “I’ve had a lot of worries in my life, most of which never happened.” He knew that there were far more worries in his head than things actually happening that were life threatening – or even truly troublesome. Tucked inside doubt is the awareness that sometimes the healthiest thing is to face fear and pain and move through it.

Consider a storm rolling across the plains. Some animals stand firm in their spot. They hunker down. Other animals move away from the rain and continue as it overtakes them. Other animals charge headlong into the turbulent weather. Which group of animals experiences the least amount of rain? Those animals who are willing (and able) to move into the storm are those who experience the least of it.

Great Awakening

Many doubters consider themselves to have had a great awakening. They believe that they figured out the great mystery of religion. Zen Buddhists believe “Great doubt: great awakening. Little doubt: little awakening. No doubt: no awakening.” That is, to really understand the world, you must have great doubt, great curiosity about what is real as opposed to the lie that our eyes and our brain tell us. (See Incognito for more on the lies our brain tells us.)

This mirrors trust. Our ability to truly trust is exposed when others are trustworthy. That is when our trust has been tested. Similarly, we can feel convinced of our great resolve of our faith only after we’ve been tested. It is for this reason that I believe that reading books like Doubt and Misquoting Jesus can help us to become more resolute in our faith.

God Is Love

It’s only fair that I share my beliefs about God and religion. Personally, I believe that every religion gets God wrong. I believe that it’s not possible for our finite and limited human condition to fully comprehend the wonder and majesty that is God. I do not believe in a disinterested God who does not care about us. Nor do I believe that he would like to know our latest tweets.

Many of the great doubters have held out the idea that there may be a god that is the universe. I believe this in that I believe that God is connected to all living things. I believe that God is love. God is the love the binds our human condition to each other. Love – or social cooperation – is what allowed us to succeed in a competitive environment where we have few assets. If you doubt me, perhaps you can develop faith through reading Doubt.