Lost Knowledge: Confronting the Threat of an Aging Workforce

Knowledge management is tricky business. I’ve spent a non-trivial part of my professional career converting tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge – well, at least one kind of tacit knowledge. This is, in fact, part of the problem. Some of what we call tacit knowledge is really implicit knowledge. That is I know something but I’ve not written down the rules or steps which lead to that knowledge. For instance, I may know the roles in a software development process inherently but haven’t codified them. (You can find where I did this for a series of articles, Cracking the Code: Breaking Down the Software Development Roles.)

Over the years I’ve codified implicit rules-based knowledge and implicit know-how types of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge – however that’s only part of the kinds of knowledge. There are kinds of tacit knowledge that we don’t know how to codify now – and others that are simply too expensive to codify. Knowledge management is therefore a tricky challenge. It comes down to not only codifying those things which can be converted from tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge but also involves those things which cannot be converted. The book Lost Knowledge: Confronting the Threat of an Aging Workforce breaks apart the problem of knowledge management and talks about the various challenges to identifying critical knowledge which may be lost in your organization as well as strategies for retaining or replacing it.

I’ve been considering tacit knowledge for a long time. Back in 2006, I was writing about how to convert tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. This is the implicit to explicit conversion process I spoke about at the top of this article. More recently I wrote a blog post Apprentice, Journeyman, Master which speaks to the kind of tacit knowledge that cannot be codified and therefore converted into explicit information.

Some kinds of knowledge are notoriously difficult to transfer. Consider the idea of transferring knowledge about how to troubleshoot a system. Bloom would say that this is a high-order appreciation of systemic knowledge – in other words, this requires a deep knowledge of a system. The kind of learning to understand a system is considered a more difficult educational objective. Gary Klein in Sources of Power argues that good decision making – the kind of snap decisions that military commanders and fire fighters must make – are inherently based on the experiences of the commanders and fire fighters. Because of that they can’t be easily transferred from one person to another. Efficiency in Learning speaks about how experts develop schemas – and how it’s often difficult for experts to communicate with novices because experts have developed more complex long term schemas for processing the information.

Lost Knowledge also acknowledges this problem but not just from the pure learning perspective, but also from a cultural perspective. Sometimes the culture of an organization makes it difficult. Perhaps the experts don’t interact with the novices so they fail to develop a bond of trust between the groups. Perhaps the organization values innovation and individuality more than reuse. (i.e. Cowboy culture) Perhaps the organization is in a place where changes are common place and therefore older experiences and knowledge are discounted in value quickly.

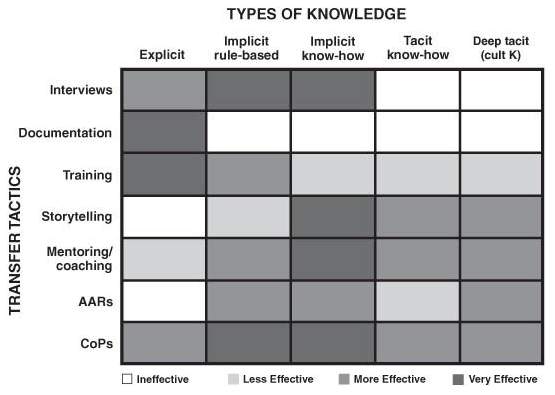

Whether an organization struggles with the culture of knowledge transfer or not; there activities that can be done to improve the transfer of knowledge. Lost Knowledge creates clarity around the types of activities and the kinds of knowledge attempting to be transferred in Figure 6.2:

Let’s take a quick look at the types of activities – or tactics that can be used to transfer knowledge:

- Interviews – Speaking with experts and recording the results. This could be in the form of audio recordings, video recordings, or transcriptions of audio recordings.

- Documentation – Obviously this is the conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge and for that purpose it’s exceedingly effective.

- Training – Training is attempting to teach the knowledge. (See Efficiency in Learning and The Adult Learner for more about that.)

- Story Telling – For thousands of years humans have communicated and passed down information through stories. We’re relatively hardwired to learn from stories. Story telling involves retelling of important experiences by experts.

- Mentoring/Coaching – Mentoring and coaching is what it sounds like. The expert mentors a replacement – or coaches a set of less experienced individuals on their learning.

- After Action Reviews (AARs) – These “Post Mortem” reviews are about the gradual transfer of expertise through the development of shared experiences and review. Experienced employees may share similar stories there by allowing junior employees to develop more abstract schemas (See Effective Learning)

- Communities of Practice – These communities are designed to bring together the best practices for a topic area. By bringing together different ideas and having a group of experienced employees talking about it, novice employees will be able to extract knowledge.

With that let’s take a quick look at the types of knowledge the book identifies:

- Explicit – Things that are specifically coded. Things that can be transferred without context through a book or other documentation.

- Implicit Rule-based – Information that can be made explicit but hasn’t been.

- Implicit know-how – Information that can be made explicit but for which there is some contextual connectivity and so therefore is more difficult to convert to explicit

- Tacit know-how – Beliefs, Intuition, and other knowledge that is difficult to codify. (See Sources of Power for Recognition Primed Decisions)

- Deep Tacit – Cultural knowledge; “how things really work”

But I’m well ahead of myself, let’s take a step back and really describe the problem. Well, it’s employee turnover. However, it’s not just any employee turnover. It is employee turnover of mid-career and late career employees and particularly turnover due to retirement. Those who are the most valuable to the organization are going to retire at some point. When they retire they’re going to take a ton of knowledge with them. In order to reduce the loss of knowledge there are numerous strategies that you can take:

- Lock older employees in – Make them want to stay past retirement age. This can be additional compensation, education about what the needs typically are in retirement (many employees retire without fully understanding how they will meet their financial needs), or flexible work arrangements.

- Develop knowledge transfer programs to transfer their knowledge to other employees. As the figure above shows, some kinds of knowledge are resistant to transfer.

- Kidnap the workers and don’t let them out. (Perhaps this isn’t a viable option.)

The book enumerates a great number of strategies for retaining employees, which I won’t repeat here. Instead, I’ll offer up that the process of onboarding new employees is expensive. Programs to reduce turnover of all employees, not just those with important knowledge, is a good way for organizations to protect its velocity in the market.

I want to leave with a parting comment. I vividly remember early in my career how difficult it was to find a job with little experience. I can remember thinking at the time that drive, tenacity, quick-wittedness, and hard work should outweigh the benefits of experience. After all, I had seen numerous people with experience that couldn’t compete with me. (Or at least they couldn’t compete with my delusional visions of grandeur.) However, I’ve begun to realize how experience can be an invaluable shortcut. Once you’ve solved a problem you don’t have to solve it again. You can review your previous answer – which can save a ton of time.

If you’re curious about how to retain and protect the knowledge that your organization needs to be successful, you should read Lost Knowledge.