Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity

No one cares what you know until they know how much you care. That truth is at the heart of Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity. Your job as a manager or leader is to bring out the best in the people you’re working with, and that means that there will be times when you need to provide constructive feedback about performance. It also means there will be times when you need to accept there are issues happening with employees, in which they need to be supported and not necessarily held accountable. Navigating these difficult waters is what Radical Candor is about.

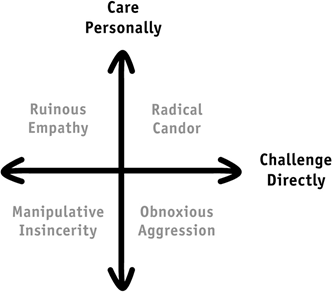

Care Personally and Challenge Directly

According to Kim Scott, there are four places you can find yourself as a manager. The measurement is along dimensions of caring personally and challenging directly.

Obviously – by the title – Radical Candor is the place Scott recommends. It involves being high on both personal caring as well as directly challenging. The problem happens when we’re not willing or able to be high on these dimensions, which can lead to:

- Ruinous Empathy – Here, you care, but you’re unwilling to directly challenge the employees. As a result, they can’t grow, because they’re not receiving the feedback they need.

- Obnoxious Aggression – Here, there’s no problem with challenging, but there seems to be less personal care. This is the place many managers can slip into as they’re driving towards goals.

- Manipulative Insincerity – Here, you’re unable to demonstrate personal caring, and you’re unable to directly challenge the employees. This results in employees who don’t trust you and in poor results.

Rather than addressing the quadrants, let’s address the challenges dimensionally.

Personal Caring

In one view, a Taylorism view, people are interchangeable cogs that exist in the organizational system. In another view, more aligned with Martin Buber and I and Thou, humans are inherently valuable because they’re humans. Personal caring starts at the fundamental level of understanding that everyone in the organization is a human. Failing to recognize people as humans who deserve respect puts you on the bottom half of the continuum. (To understand the dangers of dehumanization, see Moral Disengagement.)

The other end is intense personal care, and it’s equally hard in today’s environment. To care about a person, you must know more about them than what walks through the doors. You must understand more about their dreams, their history, and their life today. At the same time, they have a right to hold these things private and not share them with you. In most cases, there’s a degree of trust that must be built before people will share sensitive or important topics with you. (See Trust => Vulnerability => Intimacy, Revisited for more on building trust.)

Some people, particularly those who have trauma in their background, require high degrees of trust and skillful asking to receive the information about how they’re motivated and, to some degree, how you help them best. If you’re struggling to get information from someone, you may consider whether they’re traumatized, and techniques like those explored in Motivational Interviewing will be helpful, or if there’s something more challenging going on, like Intimacy Anorexia.

Challenge Directly

There aren’t many resources for being assertive. No Ego definitely has a bent towards telling things like they are – rather than being so indirect that the person you’re talking to doesn’t understand. Ed Catmull in Creativity, Inc. speaks about the brain trust, and how they’re able to have difficult conversations within the group about the quality of Pixar’s movies – as well as how this was difficult to get to. Amy Edmonson speaks about how to make safe environments in her work The Fearless Organization – but as I shared, I’m not convinced that you can entirely extract the fear from the humans who work in the organization.

Most authors counsel readers to measure their responses and consider other people’s feelings and perspectives. However, Scott encourages directly challenging people, so they know what they can improve upon. Books like Crucial Conversations are focused on having difficult business conversations, while John Gottman take a more personal and human approach to conversations in The Science of Trust.

Even with these guides, it takes courage to give feedback to others, because it means opening yourself up to feedback as well. (See Find Your Courage for more on becoming courageous.) We’re well wired to not want to admit our mistakes – as Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me) explains.

Challenging directly can only be done effectively in a relationship and where the degree of trust in the relationship allows it.

Fighting and Talking

Two people can – and do – view the same situation differently. One person may think that the two of them are talking, and the other may think they’re fighting. Some people are brought up in households where it’s not okay to disagree. In some high-volatility homes, disagreement could lead to problems; so to be safe, everything needs to be peaceful. Other families found themselves in frequent academic dialogue and disagreement that remained completely – or nearly completely – safe.

The result is that when anyone enters an area of disagreement, there are two responses. The first response of fear, and the second response of “finally.” Finally, we’ve broken through the small talk and are really having a conversation.

Conversations

Caring personally is one thing. Helping someone else know that you care personally is quite another. Certainly, approaches like Motivational Interviewing can be powerful in developing rapport; however, the degree of attention and skill necessary to use these techniques make them too difficult for most. Instead, Scott recommends that three conversations be had in sequence to create a natural context in which people can learn about the degree of caring:

- Life Story – Here, some care must be exercised to not appear to be prying and allow the employee to avoid sensitive or painful areas until later, when trust has been established.

- Dreams – Here, the key is to ensure you get to the dreams that don’t include working for the company or the manager. They need to be the real dreams that are often left unstated.

- Eighteen Month Plan – Here, the employee works on a specific plan to move them forward towards their dreams – even if it’s outside the company.

These are conversations that are intended to be worked into the employee’s regularly scheduled, 1:1 meeting but can be scheduled as separate conversations as well. The point isn’t how they’re scheduled but that the manager focuses on the individual’s history, hopes, dreams, and fears.

Sails and Keels

The most visible part of a sailboat and the thing for which the sailboat gets its name is the sail. However, no boat can operate with just a sail. Sailboats need the hidden but critical keels. These are weighted fins that descend into the waves to keep the sailboat upright. A sailboat without a keel will tip over in a gentle breeze.

Like sailboats, organizations need the super-stars who are ambitious and driven. It also needs the steady people – who Scott calls “rock stars” after the Rock of Gibraltar. Scott’s rock stars are the keel, preventing the boat from flipping over. Conversely, a boat with a keel but no sail doesn’t have anything to propel it forward. The super-stars, in Scott’s language, are like the sails that propel the organization forward.

Managing Other People’s Emotions

One of the mistakes that managers can make is attempting to manage the emotions of others. Whether that is walking on eggshells and being overly gentle with feedback, because you live in mortal fear of making someone cry, or something as subtle as cancelling meetings more aggressively when someone is in a bad mood, you can’t manage it.

You cannot fear other people’s emotions, but you can’t decide that you can control them either. Other people are entitled to their feelings, whether you like them or not. Perhaps if you want to find a way to both care deeply and challenge directly, you should find your Radical Candor.