Change Intelligence: Using the Power of CQ to Lead Change That Sticks

That there are different kinds of intelligence is not a new thought. Barbara Trautlein wants you to know about change intelligence and why it’s important.

Multiple Intelligences

Before we can get to the idea that some folks may be predisposed to a certain kind of intelligence, we’ve got to go back to Howard Gardner, who first proposed the idea. In short, the idea is that we can be very intelligent in one way but not another. This led to a branch of thinking about whether emotional intelligence might be one of them. Daniel Goleman wrote a book titled Emotional Intelligence, which was very popular and brought the idea to people’s attention. Others have picked up on Goleman’s work, including Travis Bradbury and Jean Graves, who wrote Emotional Intelligence 2.0.

Others have found ways to explore other kinds of intelligence, including Conversational Intelligence. There are others who use intelligence in their title – like Collaborative Intelligence – but don’t mean it in quite the same way.

CQ

One of the conventions that happened is intelligence quotient began being abbreviated as IQ, and therefore emotional intelligence became EQ and Trautlein’s change intelligence became CQ. While IQ has a scale and a measurement with it, neither EQ nor CQ have a scale. (Interestingly, our collective average IQ keeps going up according to the Flynn Effect, as explained in Range.)

EQ has either five or four key components depending on which variation of the work you are focused on. These components, however, do not have specific set of objective metrics. They’re guidelines for ways to improve. While some have developed assessments around EQ, there isn’t one standard way to measure it.

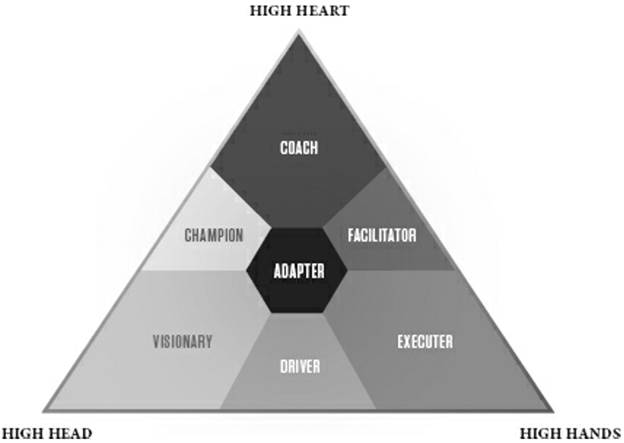

Trautlein’s CQ is different still, having three areas of focus or interest: head, hand, heart. In her assessment, you’re given forced-choice questions that ultimately lead you to choosing one for the various scenarios that you’re presented. The relationship between these three places you into one of seven categories, including the “pure” single-attribute versions, the “mixed” two-attribute versions, and the single three-attribute version. The graphic that she uses is:

Because of the forced-ranking nature of the test, there’s no improvement in capabilities in each of these areas, just a pull in one direction or another.

Personality Testing

There’s a great deal of interest in psychological typing systems, as explained in The Cult of Personality Testing. I’ve reviewed several books about different personality profiling systems, including Personality Types, The Normal Personality, Fascinate, and Strengths Finder. I cautiously advocate the use of these personality profiles because of the “Barnum effect.” The short version is that people tend to identify with profiles and horoscopes more than they should given their non-specific nature. (See Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology for more.)

Despite the tendency to apply more weight than is deserved, they can serve as a useful window to discover more about yourself. That’s why we suggest that people consider doing a few of them and seeing how it exposes aspects of their personality that they may not have been aware of in our Extinguish Burnout materials.

Systems

Beyond Trautlein’s assessment model, there is a keen awareness of some of the dynamics that affect corporate life. She describes the three layers of change – executives, management, and workers – in a way that is strikingly similar to the way they’re described in Seeing Systems. Each part of the organization sees itself as acting rationally and can’t understand why those around them are acting so oddly.

Executives wonder why the managers and workers aren’t implementing their beautiful strategies. Workers are wondering how the executives could have conceived of such an ill-informed strategy that doesn’t match the way things really work. The managers are stuck in the middle trying to figure out how to get more compliance with the strategies without alienating the workers and how to tell the executives that their strategies aren’t grounded in reality.

Planning Now

General Patton’s rule, “A good plan executed today is better than a perfect plan executed at some indefinite point in the future,” is a good way to express the need to be done. It’s the mantra of satisficers everywhere who recognize that there isn’t time for perfect. (See The Paradox of Choice for more.) Too often, we believe that we can plan sufficiently to identify every condition and handle every case. However, as Colonel Tom Kolditz, the head of the behavioral sciences division at West Point, says, “The trite expression we always use is ‘No plan survives contact with the enemy.'” (See Made to Stick for more.)

In other words, do enough planning to generate value and then try to use it so you can learn what works – and what doesn’t.

Fear

There is one emotion that derails change most, and it is fear. We’re afraid of the present, we’re afraid of the transition. We’re afraid of failing and afraid of succeeding. People are afraid of what the future holds and of remaining the same.

Too often, change leaders fail to recognize the power of fear. More importantly, they fail to recognize how easy it is for people to become fearful. Fear is more prevalent and powerful than any of us would like to believe. However, you shouldn’t be afraid to read Change Intelligence.