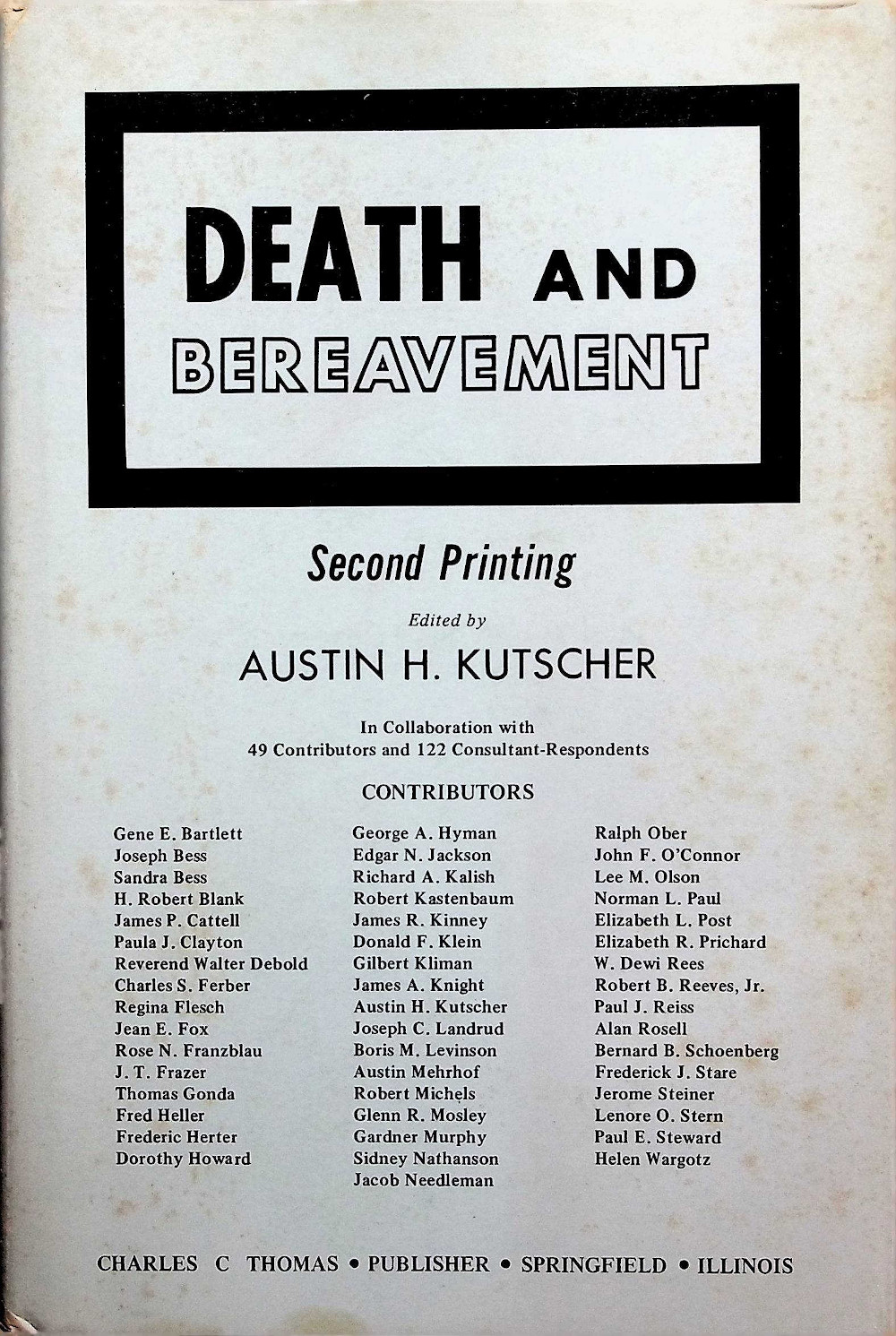

Death and Bereavement

It cannot be escaped. Death will come for each of us, and, invariably, it will come for some of those we love before it comes for us. That’s why Death and Bereavement is an essential topic. We’re not going to avoid it, so we should be prepared.

When Death Beckons

There’s a great deal of turmoil over the idea of suicide for those who are terminally ill and in pain. I certainly understand the desire to not encourage suicide, but I also recognize there may be appropriate times to allow this option. (See Undoing Suicidism and Final Exit.) It’s hard to argue against the idea that someone in pain should be allowed to end their suffering. Similarly, shouldn’t we allow people to die if they’ve become a burden on their friends and families? The ethical issues are tricky to be sure, but not having an option seems cruel.

Death Prediction

We have certain expectations about the world that allow us to predict the future and therefore feel safe. (See The Righteous Mind and Mindreading.) Sometimes, our predictions and expectations come into question, and that can cause a crisis. When we see deaths in the elderly, we expect that we’re not the name on death’s list. We can safely ignore it for a bit longer. (See The Denial of Death and The Worm at the Core for more.) However, when someone younger than us dies, we recognize that death isn’t working as it should. We have a violated expectancy (using the words of Gary Klein in Sources of Power). That violated expectancy causes us to reevaluate our situation.

Bereavement Overload

Even when death is behaving as expected, it can still be overwhelming. Elders discover that the death of their family and friends comes at a pace that exceeds their capacity to cope. Certainly, death is expected, but the frequency can be challenging. Too many changes to process in too short of a time.

This often leads elders to seek solace from the younger professionals that they interact with, but those professionals often feel unprepared to support the elders, having minimal (if any) training and not enough life experience to impart wisdom.

The Grand Rounds Illusion

The powers of medicine to improve and prolong life are quite impressive, and it’s easy for professionals coming up in the field to expect that medicine can solve any problem. They believe, naively, that doctors can solve any problem. It’s not long after contact with the real world that the cracks begin to appear and the illusion breaks. The resulting disappointment in medicine can leak out in every direction, with doctors frustrated at nurses and nurses frustrated with doctors.

It can even sour the relationship with a patient – or patients in general. A nurse or doctor may feel guilty that they cannot solve the patient’s problem. They may even be angry with the patient for dying, because this makes them feel helpless and ineffectual. It’s hard to separate these feelings that come as a result of trying to help – and occasionally failing. It’s not their fault, but we want to find someone to blame.

If Love, Then Sorrow

Saying that the pain and sorrow you feel is a signal of the love that you felt for them isn’t any solace in the moment. However, as it adds to our understanding, we should expect that there will be sorrow any time there is love. We should expect that the moment of death and the surrounding times preceding and following the death should be filled with sorrow. To expect something else is to deny our humanity, our ability to love, and our need to grieve.

Sympathy and Empathy

Too many people receive sympathy at the death of a loved one when what they really need is empathy. Sympathy is “Sucks to be you” where empathy is “I understand this about you.” One separates, and the other connects. What we need most during bereavement are people who are connecting with us, since an important relationship has just crossed to a place without any connection. (See I Thought It Was Just Me (But It Isn’t) for more.)

Abandonment

It’s natural to believe that the deceased abandoned us. This is particularly true when the death is by suicide. We wonder how they could leave us here alone. (See Loneliness.) However, sometimes the loneliness that we feel – that sense that no one cares – is a tragic illusion. Imagine the tragedy of having a funeral for a child. Heap on top of that a sense that no one came. In one of the stories that was recounted, a father felt abandoned by his community, because people didn’t come to the funeral or visit him afterwards. His perception of the events was different than the factual record of many people at the funeral and a relatively constant stream of people visiting with him for months.

Ashamed of Death

For many, as Alvarez says in The Savage God, death is more taboo and less discussed today than sex was during the Victorian era. That represents a problem if we want to be able to work through our fears about death and confront them. When adults are ashamed to speak of death, then children know that it should not dare cross their lips. They’ll have to bury any fears and concerns about death to prevent accidentally crossing a cultural line that children aren’t allowed to cross. It’s only through transparent conversations that we can remove the stigma. (See Stigma for more.) Ultimately, we want to be as open as possible about Death and Bereavement.