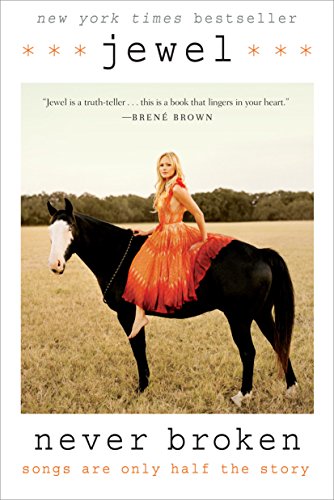

Never Broken: Songs Are Only Half the Story

I was born with a genetic defect. It’s never been officially diagnosed, but I know it’s a limitation. I’ve been born without the “fan” gene. That is, fan in its real meaning of “fanatic.” I knew Jewel’s music and appreciated it. Music is for me like air. If there’s not music playing around me, it’s playing in my head. My musical tastes are what others would call eclectic. Jewel’s music made it on my likes list – which is much shorter. Never Broken: Songs Are Only Half the Story is her story of growing up and being grown up. I would have never found it except through my research on trauma and the book The Myth of Normal, which references it.

The soulful stories that exist in Jewel’s songs come from deep exploration and much trauma. Her challenges with her parents are at least an order of magnitude more than mine. (See Fault Lines for more about that.) Her story is about struggle, loneliness, heartache, and ultimately triumph. What intrigued me about the book more than any other thing is how she found a path of growth instead of one of numbing. (See Transformed by Trauma for more on growth post trauma.) Never Broken is an opportunity for her to share her love of people and compassionate desire to minimize their suffering.

A Few Parallels and Lots of Differences

I won’t go into the complete story, because the book does a wonderful job – and it’s her story – but I will say that there were times that I felt resonance with Jewel’s experiences and other places where we clearly walked radically different paths. I left home at 18, not 15, and I’ve never been homeless. And at the same time, there were echoes that were deeply stirring as I considered feelings of loneliness, making strong decisions, figuring it out, generational trauma, divorce, and more that resonated.

As I share my story woven with hers below, I do so as an example of how we all face traumas – some are the same as each other. Some traumas we face are uniquely ours. However, we can view traumas as similar enough to connect and support each other.

Loneliness

I related in my review of Loneliness that being alone and being lonely aren’t the same thing. I’m no expert on Alaska but my visit and the feedback make it clear that there are times when people are alone. However, Never Broken doesn’t talk about loneliness in that way. The loneliness that Jewel speaks of is that sense that you’re not understood. It’s the sense that the world you live in is foreign to others and almost as if you speak a different language.

In Straddling Multiple Worlds, I share a few aspects of how even being in multiple worlds instead of one can be alienating and difficult. The reason for your disconnect could be that you’re struggling to get by in a world of the affluent, or that you’re thinking in ways that aren’t “normal.” Feeling like you don’t fit in is deeply alienating and ultimately lonely. It’s even more separating and lonely when you have the courage to stand for your convictions.

Strong Decisions

There are a few very key, defining moments in my life that I know were important. One was when I was in Boston and visited the Church of Scientology. (I explain this in my review of The Paradox of Choice.) Another was the time I decided that I could be afraid but that I refused to live in fear. Jewel rightly points out decisions in her life that made the difference. She explains about her decision to be honest in her writing when she couldn’t be with people. She also explains the decision not to take someone up on a proposition even when the money was sorely needed.

These sit alongside her decision to not drink or do drugs. She aptly states that you can’t outrun your pain. You must go through pain – not around it – and not run ahead of it. It will always find you.

These are simple decisions that are hard to make. (See How Good People Make Tough Choices for more.) I deeply admire people who find the courage to make these hard choices and live true to themselves – or as true to themselves as any of us get. (See Find Your Courage for finding this kind of courage and how to enable it in others.)

Figure It Out

One of the greatest gifts that I’ve received from my upbringing is the belief that I can do anything I set my mind to. Obviously, there are limits. I’m not going to be a test pilot or an astronaut at this point, but within reason, I can do almost anything. The idea that you can figure stuff out comes from a sense of necessity. For Jewel, it may have been that Alaska requires it of everyone. I’ll certainly buy that, given it’s still a relative frontier. For me, I don’t know where it comes from. Maybe it was just seeing my dad figure things out and make things work.

In some circles, it might be called self-esteem or self-confidence. However, that doesn’t really capture it. It’s not that you don’t know you’re going to try and fail and try and fail again. It’s that you know if you’re willing to work at something, eventually you’ll find a solution. Carol Dweck would call it a growth mindset. (See Mindset.) Angela Duckworth would use the word Grit. Roy Baumeister would say Willpower. Rick Snyder would call it hope. (See The Psychology of Hope.) Margie Warrell might call it courage. (See Find Your Courage.) Whatever you call it, it’s a force to be reckoned with.

Generational Trauma

Trauma is whatever you struggle to process and integrate into your understanding. (See The Body Keeps the Score.) Sometimes, it’s things that should have never happened to you – but they did. From the point of view of the person whom trauma is inflicted upon, it’s hard to recognize that the people who are the perpetrators of the trauma have had their own trauma in their lives. It doesn’t excuse or make right their behaviors, but it does help you accept them as an unfortunate but natural consequence. (See How to Be an Adult in Relationships for more.)

The greatest gift that we can give future generations is to break the cycle of trauma. We can do the hard work to achieve the personal growth that allows us to prevent the ripple of trauma from moving forward. Jewel notes the work that she and her father have done to dampen the impacts of generational trauma.

Divorce

I explained in my review of Divorce both its causes and its consequences. Since then, I’ve written about The Progression of Parental Alienation and The Psychology of Not Holding Children Accountable. It addresses what Jewel calls “The Disneyland Effect,” where parents try to “win” the children by giving them things and experiences to become their favorite. Cruelty isn’t what it does to the other parent. Cruelty is what it does to the children who are “forced” to decide between two people they love and who love them.

Emotional English and Worthy of Love

We have formed unspoken beliefs about emotions – whether they’re good or bad. The trick is that most emotions are what the Buddhists would call non-afflictive. (See Destructive Emotions.) Sometimes, we need to work around what we learned as children and accept our emotions. (See Emotion and Adaptation and How Emotions Are Made for more.) The greatest tragedies I’ve seen are related to people who believe that emotions are bad instead of teachers that are sent to keep us safe.

Sometimes our emotions are so compartmentalized, hurt, or broken that we can’t experience love the way that we should. (See Anatomy of Love, Daring to Trust, and The Art of Loving for more.) Until we can accept that we’re worthy of love and learn to love ourselves, we’ll find it hard to accept love from others. (See No Bad Parts for more on accepting all the pieces of us.) In The Science of Trust, John Gottman, relationship guru, explains the things that get in the way of relationships – and being loved by others.

Digging Back to Your True Self

You are not broken. You’re just buried in the trauma, pain, armor, and busy-ness of life. That’s a fundamental message of hope. Too many people see the things in their life – including their behaviors – and they’re tortured by the shame of not being enough. Somehow, they missed out on the magical elixir that would allow them to be a normal human being. Somehow, they feel as if they’re broken beyond repair. The view that it’s not you who are broken but rather that your true self is buried beneath other things is freeing. You can, given time and effort, dig yourself out. If you’re broken, there’s no telling if you can be fixed – or not.

Hard Wood Grows Slowly

There are lessons in nature. One of them is the nature of trees. There are, of course, many different kinds of trees that grow at different rates. Many of the things we have that are made from wood – like the 2×4 studs in our home – come from pine. Pine grows quickly, but it’s easily broken. Quality furniture, things that are meant to last and be cherished, are made from hard woods – and they grow slowly. The slow, hard path isn’t the one that people want to know – but it is the one that is lasting.

I’ve read plenty of books about how to get there quick – and why you need to do it. Launch carries the subtitle, “The Critical 90 Days from Idea to Market”. Traction caries the subtitle, “How Any Startup Can Achieve Explosive Customer Growth.” I believe in hard work. I believe in making decisions that lead to the long-term results I want – even if the short-term results aren’t great.

Jewel recounts her deal with Atlantic Records. Little up front, just enough to get her off the street. The largest back-end deal made at the time. She’d get more if she sold more. It’s a perfect example. I did the same thing when I made my deal to sell courses through Pluralsight. The largest back end available with almost no advance. I wanted a way to make the long-term work, even if it meant working harder in the short term.

Angels in my Life

Jewel recounts stories of what she calls everyday angels. (A term her fans coined.) They’re people whose words or deeds helped her at a critical moment. They helped her to grow. These people may have realized the impact they had – or they may not have. Either way, the impact was made by “Indian Uncles” and concerned friends. We all have these everyday angels in our lives. They don’t arrive on a beam of light, nor stand with a blazing sword before us. Instead, they come into our lives to enrich it.

I’ve had several of these people myself. Some have stayed for the better part of my adult life. Many have come for a time and are no longer an active part of my life in the physical sense. However, they’ve shaped my path and lifted me up in ways that aren’t possible to explain.

We (Terri and I) try to be everyday angels. Offering our home for people to stay with us. Making all the Extinguish Burnout materials free. There are dozens of small and large ways that we try our best to bring more everyday angels into existence, using Gandhi’s guidance to be the change we want to see in the world.

Audiences Don’t Care If You Sing Correctly

They want to feel something. It doesn’t matter if you get the words, the melody, or harmony right (within reason). What they care about is that, when they leave, they’ve experienced (or felt) something. For over a decade, I ran live sound at church at least one weekend a month. I learned so much about production with great people. I realized how little what we wanted to do mattered compared to what we actually did. The people in the audience didn’t know what was “supposed to happen.” They just wanted to feel like it happened with them.

I learned so much about how bass can connect people to a rhythm. Kick drums and electric bass keep the time. If you dump more of that into the house (the sound that goes to the audience), you synchronize them to what is happening on the stage. A weak voice can be amplified. Short reverb can cover a vocal talent who is struggling to finish a set. A good equalization can make the difference between hearing the vocals and having the piano (or the guitar) running all over the place.

I was lucky enough to begin to see the big waves that we were creating to unite people and help them feel connected with one another – our fundamental human need.

It’s this experience that made Jewel’s discussion about having the right band make so much sense. Drummers have click tracks to tell them how to keep time – but it prevents them from adjusting to the natural tempo of the crowd. Counting measures works when you’re playing a specific song a specific way, but it prevents you from doing the chorus again when the crowd starts to sing along. I so appreciate good “crowd work” (reading the crowd and adapting). I loved that Jewel related both the benefits and the struggles.

Tightly Packed Day

In the maid’s quarters in a house on Center Avenue in Bay City, Michigan, an alarm has been going off unheard for 20 minutes. It’s the kind of wake-the-dead alarm they can hear in the kitchen two floors down, but I’m just starting to stir. I’d get up and go to high school before heading out to work and finally ending my day at the local college. My high school work was light. Work was 20 hours a week. I was carrying 10 credit hours a semester at college – filling all my weeknights. I spent 15 weeks sleeping maybe four hours a night, and I was doing my homework and studying in other classes and during every scrap of time I could find.

I can identify with “I had a tightly packed day, and went about it with a starving man’s mentality, devouring everything in sight.” I can also identify with “I was too busy surviving to cry in Anchorage.” There were no margins. There was nothing left. I had every moment spoken for. I carried the Thoreau quote, “Who can kill time without injuring eternity” on my lips everywhere I went.

What is too easily dismissed in my experience is the value it brought. I knew that I could do it. The memories of these times have reminded me that even in very busy parts of my life, it will end. It is a defining moment when I can point to hard work and the payoff.

Bifurcated Sense

Some of the people who seem the most confident are those who are mostly deeply insecure. Their image of confidence is an illusion they project – to others and themselves. There is a split between the person they want to appear to be – even to themselves – and their deep-seated fears. This projection itself drives people to experiencing impostor syndrome. The resounding question is, “When will they find out that I’m not really who they believe I am?”

The more common experience of a bifurcated sense of being is an oscillation. It’s the result of the inner battle of the mind. One moment, there’s a self-correction to combat the overly critical inner voice. The next moment, the inner critic is going after the voice that elevates parts of you to the grandiose. Sometimes, these battles are epic, as the parts of your psyche fight for control. No Bad Parts would speak of our hurt places, the protectors, and the exiles locked in a battle for control.

My language is integrated self-image. It’s a way of viewing our self that accepts the good and the bad instead of trying to argue for all good or bad. Instead of each part of us feeling invalidated, it can be acknowledged as a part of the whole. (See Braving the Wilderness for more.)

Feeling Proud

When your sense of self is disrupted, it’s hard to be proud. What are you proud of? The constant storm of emotion and thought that pervades your existence? Even when you’re working hard and you’re being rewarded for that hard work, it’s difficult to accept it. It’s disconnected from your experience somehow. Jewel’s graduation may have ended with her throwing away her diploma (she’s not sure). Here’s a symbol of achievement – in her case, a monumental achievement – but it couldn’t be accepted, because it wasn’t consistent with her internal view. Some of the rationalization was that she wasn’t in a position to have much stuff – but that was a rational lie (which she acknowledges).

Behind the rationalization was the quiet reality of parents who couldn’t give Jewel what she deserved. A mother who was absent and a father battling with his own demons didn’t have the capacity to support her in ways that would remind her that she was good – that she was enough.

Enough

The opposite of scarcity isn’t abundance. The opposite is enough. (I gave a talk on this topic Enough Scarcity in 2017.) Feeling like we’re “enough” is a common challenge. Brené Brown talks about it in I Thought It Was Just Me (But It Isn’t), and Gabor Mate explains his struggle with it in The Myth of Normal. The key question is enough for what? The tragic answer that cannot be spoken is often “to be loved.” It’s tragic, because it’s a sign of a fundamental lack of understanding about what love is. Love should be your birthright. It’s not something to be earned, bartered for, or taken.

In English, the word “love” is overloaded. Consider that, in Greek, there are three words that are all translated to love in English – agape, philos, and eros. I’ll dispense with eros because it’s romantic or physical love. (See Anatomy of Love for more on this kind.) Agape, global love, and philos, brotherly love, are the two most commonly considered, and the line between them isn’t always as distinct as we’d like. (See My Spiritual Journey for more of the Buddhist perspective.) C.S. Lewis also speaks of different kinds of love in The Four Loves. When we speak of love in English, we’re often not clear. In the context of “enough,” the meaning of love is “to be cared for.” Parental love is what it might be called.

Parental love is supposed to be unconditional caring. Too often, children don’t experience love from their parents in this way. It’s often inconsistent. Sometimes, instead of love and care, they receive cruelty and abuse. As a result, their perception of whether they are enough or not is often hampered if not destroyed.

Underneath the need for love, we see a need for safety and our avoidance of death. (See The Worm at the Core for more about how death drives us.) We equate love with safety, because we only became the dominant biomass on the planet by our unique ability to work together. (See The Righteous Mind.) One might slip here from love to acceptance as a more basic form. If they accept me, they won’t expel me from the community. This would be catastrophic. While in today’s world, we aren’t ejected from communities like we once were, the fear still lingers. At some level, we wonder whether we’ll be left alone to die if the community doesn’t accept us.

More than any other creature on Earth, we’re unconsciously aware of our need to be connected. That’s why loneliness can be so frightening. (See Loneliness.) Like much of life, it is our perception of loneliness, unlovability, and acceptance by others that matters. The objective truth isn’t the point. Consider, for a moment, the number of celebrities who have died by suicide and how they are loved – or at least accepted – by so many.

Support and Solidarity

The opposite of loneliness is finding the person who wants nothing from you but believes in you. You feel heard and seen not for what you can do for someone but because they understand your struggles at a level that most aren’t capable of. There’s a song by JJ Heller, “What Love Really Means”. The chorus contains the words, “Who will love me for me // Not for what I have done or what I will become.” It’s in this sentiment that I believe we move from just acceptance to love.

Acceptance is fundamentally rooted in a belief that you subscribe to the same social norms that I do – or that I believe your deviances from what is socially acceptable are offset by what you may be able to do for me. This may be a clue to the tragedy of artist suicide. For them to express their creativity, they must necessarily deviate from the norm. (See Creative Confidence for assurance we can all be creative.) Innovators face similar asymmetry. They are lauded for their innovations and criticized for their disruption and deviation. (See The Disruption Mindset, The Innovator’s DNA, The Art of Innovation, and Unleashing Innovation for more.)

When the balance for innovators is in favor of the benefits, they find acceptance. When their ideas are more disruptive than valuable, they’re summarily dismissed. The support that they feel is conditional. We’ve seen a gradual deterioration of loyalty over the years. (See Exit, Voice, and Loyalty for more about loyalty’s importance.) Robert Putnam spoke about the societal decline in Bowling Alone, and Francis Fukuyama spoke about corporate loyalty decline in Trust: Human Nature and the Reconstitution of Social Order. In short, we’re seeing an erosion of real support and solidarity over the long term – and that’s why when you find it, it’s so special.

Innocence Traded for Wisdom

For a commercial project, I reviewed a book in progress recently. It was focused on the loss of innocence and the tragedy that it was to lose your innocence. I pushed back, because I believe that we’ve lost our innocence long ago. I believe that we have our first event, and when we experience it, we’ve lost our innocence. It’s our first heartbreak that takes that innocence. However, a key point that was missing that Jewel relates eloquently is that innocence is traded for wisdom. It’s a beautiful reminder that when we lose something, there is often something else there to take its place. One of the pieces of wisdom I hope you’re able to take away is that, no matter what has happened to you, you’re Never Broken.