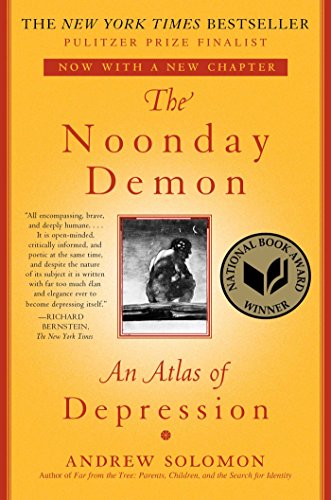

The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression

If you’re going to be navigating something, it’s helpful to have a map – or even multiple maps. For navigating depression, Andrew Solomon gives us The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression. A depression sufferer himself, he walks us through his personal experience, the experiences of those he interviewed, as well as a selection of the research on the topic of depression. At times, the experiences and research appear to differ. Even two people’s stories seem to point to different ways of experiencing depression. In the end, Solomon exposes that what we call depression may be a cluster of similar maladies with a variety of factors leading towards them.

What is Depression?

It’s a good place to start. Defining what depression is – and isn’t. Of course, the DSM-5 has a definition for a major depressive disorder. However, for most, including psychologists, this definition fails to capture the state well. It leaves lots of gray areas between what’s “normal” and what’s “abnormal.” Solomon describes depression as a flaw in love. “To be creatures who love, we must be creatures who can despair at what we lose, and depression is the mechanism of that despair.” He clarifies later, “Grief is depression in proportion to circumstance; depression is grief out of proportion to circumstance.”

Herein lies the rub of depression: assessing the circumstances. We’ve learned that some of the best ways to combat depression don’t change the circumstances. We find that the best treatments for depression change the way we view the same circumstances. What’s proportional to one may not be proportional to another.

Later he admits, “Depression? It’s like trying to come up with clinical parameters for hunger, which affects us all several times a day, but which in its extreme version is a tragedy that kills its victims.” We can map out the extremes of hunger – malnutrition – and the extremes of depression – major depressive disorder – but separating the normal from the abnormal or the proportional from the non-proportional is much, much harder.

The Impact

Depression is bad in that it prevents people from feeling good. One of the preeminent markers is an inability to experience happiness or joy (anhedonia). However, what’s the real impact of depression beyond the loss of happiness and joy? It’s the leading cause of disability for persons in the United States over the age of five. Fifteen percent of people who are depressed will eventually die by suicide – compared to 14.5 per 100,000 overall. (Thus, this is 1,000 times increase in probability of suicide).

The How of Happiness quotes the World Health Organization as believing that depression will be the second leading cause of mortality and impacting 30% of all adults by 2020. (Obviously, this was prior to 2020.) Some place the estimated impact of depression through lost work and treatment at over $200 billion dollars annually. It has a real impact on economies across the globe.

The Cause – Biology?

With the advent of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), it seems like depression might be caused by a lack of enough serotonin in the brain. Supplements seek to increase the levels of 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), a key precursor to serotonin. There is some research that shows that these have impacts. However, some are still appropriately concerned and critical of the impact of changing brain chemistry, including William Glassier in Warning: Psychiatry May Be Hazardous to Your Health.

Work continues to find genetic markers that lead to depression. Research seeks to separate genetics from environment in an effort to focus on the key factors that lead to depression. Meanwhile, we’ve begun to discover that genes don’t work on their own. In The How of Happiness, Sonja Lyubornsky explains that roughly 50% of our happiness comes from a genetic “set point.” This is consistent with others, including Judith Rich Harris, who explains that our children’s behavior may be similarly influenced by genetics at a level of about 50% in her books No Two Alike and The Nurture Assumption. In short, biology is not destiny. Certainly, we see genetic factors in everything, but we are beginning to realize that many of our genes require activation from the environment.

The Cause – Environment?

It was a landmark study. It coded childhood experiences – adverse childhood experiences – and tallied them. The results were striking. Those adults whose childhood was wrought with more adverse experiences had worse health. In How Children Succeed, Paul Tough explains that the higher the score, the worse the outcomes. However, that’s not the end of the story. The trauma that leads to poorer health can precede birth.

In Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, Robert Sapolsky highlights the work of David Barker, who was able to show that long-term health could be impacted by the stresses that a mother felt during pregnancy. His research seemed to indicate that if the mother was stressed, the child would be predisposed to perceiving the world as stressful rather than safe.

Other research seems to indicate that if we constantly trigger the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is our response to stress, it may get stuck “on.” In other words, exposure to stress can make us more likely to see stressful things – even when they don’t exist. This is somewhat mediated by Richard Lazarus’ work as chronicled in Emotion and Adaptation. (Lisa Feldmen Barrett in How Emotions Are Made expresses similar experiences). The point of Lazarus’ work is that we see stressors and then we evaluate the stressor in comparison to the possible outcomes, their probability, and the impact. This is divided by our capacity to cope. The result is the degree to which we’ll feel stress in the situation. Even in stress the way that we think about it – our controllable cognition – plays a huge role. It may not eliminate the stressor, but it can change the impact it has on us.

Perhaps depression isn’t about our genetics – or our environment – but rather is some interaction between the genetics, our environment, and how we perceive it.

Relating to PTSD and Post Traumatic Growth

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is fairly-well known now. However, the function isn’t as well understood. PTSD comes from a traumatic experience that an individual has been unable to fully process. PTSD is subjective. What is traumatic and cannot be processed by one might be processed by someone else just fine. It’s not a failing, it’s a mismatch between the developed skills and the perception of the events. The secret to PTSD recovery is helping the person learn how to process their experience more completely.

Post-traumatic growth (PTG) is another option for situations where trauma has occurred. It’s processed, and the person is changed, for the better, as a result of having gone through the trauma. It doesn’t mean that they’d want to incur the trauma again or that it was pleasant, just that they’ve found a way to become better through it.

Solomon explains depression in this way for him. He’s found that he’s grown through his experiences with depression, no matter how much he may have wished not to have had to suffer.

Loneliness

When I reviewed Loneliness, I shared the dance that loneliness and depression are in. Solomon agrees. He sees depression as causing loneliness and vice versa. Those in depression find themselves separated from others by an invisible wall. They can see that there are others around, but at the same time, they feel separate and apart. When you find loneliness, look, and you’ll find depression. Where you find depression, look, and you’ll find loneliness.

Perfectionism

As a goal, perfect isn’t bad. It’s perfection that Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool were talking about in Peak: purposeful practice in the pursuit of perfection. The problem is what Barry Swartz in The Paradox of Choice explains drives people to be less happy. Maximizers – those who must have perfection – are less happy than those who are more likely to satisfice – settle for “good enough.” We all have some times when we maximize, we’ve got to have it perfect. The trick is that when we expect we must be perfect, we will invariably fall short, so we’ll be disappointed in our performance, and that is one step away from depression.

Burnout and Depression

It’s time for a slight side-step from Solomon’s work to explain an important relationship between burnout and depression. Research shows that burnout screening is an early indicator for future depression. They’re not fundamentally different – but they’re different. Both are driven by feelings of inefficacy. The difference with depression is a sense of futility. In short, “What does it matter?” This is not something that we typically see with burnout but is present when people are depressed. (For more burnout/depression resources, see everything that we’ve got available at https://ExtinguishBurnout.com – almost all of which is completely free.)

Like most things in mental health, there are probably those who are burned out who are wondering about the futility of it all, and those who are depressed who understand the meaning of life. However, as a general rule, a quick way to separate the two is futility.

Hopelessness

At the heart of both burnout and depression is a sense of hopelessness – that it can’t get better. It will never be any better than the current moment. The situation is permanent. It’s pervasive throughout someone’s life, not just the current situation. It’s also personal. It’s not caused by other factors, it’s a result of the person that someone is. The problem is that these views aren’t right. (See The Resilience Factor for more.) The problem is that things do change, it’s not permanent. No situation is universally pervasive, and it’s rarely as personal as we believe.

C. Rick Snyder in The Psychology of Hope explains that hope isn’t a feeling, it’s a cognitive process made of waypower – knowing how – and willpower – desire or commitment. (For more on willpower, see Willpower.) When we see people who are hopeless, we often find they don’t know “how” things could get better. Some degree of cognitive constriction may lead people to overlook the ways that things may get better on their own, what they may be able to do to make it better, or simply how the situation can be changed. It’s this same cognitive constriction that can lead to suicide, as The Suicidal Mind points out.

Suicide by HIV

Solomon admits that his intent was to die via AIDS. He was trying to commit suicide but in a way that made it seem not like suicide. This is at the heart of the challenge with identifying suicidal behavior. Inferring intent – when someone doesn’t write a book about it – is hard. (Only ~1/4 of people even write suicide notes; the odds of writing a book on depression are substantially smaller.) In some cases, intent is clear, but in many others – like Solomon’s attempt – intent is very unclear. (See Suicide: Understanding and Responding for more.)

We don’t track statistics – even if we could confer intent – on rare forms of suicide. Instead, we must realize that there are many, many ways to kill oneself if someone wants to – and it makes stopping someone from committing suicide very difficult. (See Suicide: Inside and Out for more on how difficult suicide can be to prevent.)

Weakness of Character

Depression, suicide attempts, and mental health issues are often seen not as illnesses but rather weakness of character. It’s as if others believe that what’s lacking is willpower – not that there’s something wrong for which someone can’t be held accountable. In Willpower, Roy Baumeister explains that it’s an exhaustible resource – something that everyone has limits on. The introduction of SSRIs may have strengthened the medical model for depression, but as we saw above, it’s not enough, and people know it.

Never has someone said that it’s a weakness of bone when someone walked in with their arm flapping after a break. We don’t call people weak-hearted as they’re having a heart attack. Yet somehow, we believe that we should be able to control our mental health in ways that we can’t manage our physical health. It’s been a long time since we believed that illness was a plague brought upon us by God. Instead, we follow a biological germ theory of disease that says we were infected – not that God is inflicting suffering on us through physical illness.

There’s a serious schism of accountability and responsibility for mental health when compared to physical health. In short, we don’t give people who struggle with mental health a fair shake.

Low Side Effects

Treatment with SSRIs isn’t because of their overwhelming efficacy. They have low double-digit margins of efficacy over a placebo. Solomon makes the valid point that they do help some – but that doesn’t excuse dispensing them via a PEZ dispenser. We prescribe SSRIs with very little concern – in part because they have a relatively low side-effect profile. Sure, there are sexual dysfunction concerns, but 99% of people with acute major depression report sexual dysfunction anyway.

At some level, SSRIs and other potentially addictive drugs are something to try. If you can’t mitigate the pain, you’ll have trouble getting to a point where anything else will help. Often, a pill is quick and easy. Treatments like ECT (Electro Convulsive Therapy) and its newer cousins offer quick relief but there are still some concerns about side effects. Talk therapy, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), have been shown to be effective – but they take a long time. In many ways, SSRIs and other medications are “the easy button.”

Substance Abuse

Chasing the Scream and The Globalization of Addiction do a good job at fighting back the pharmacological theory of addiction – that is, the substances make you do it. Growing up in the 1980s, I was told that just one hit could start an addiction. Nancy Regan told us to “Just Say No” to drugs – and it didn’t work. The uncomfortable truth – for everyone – is that substance abuse is a solution to a different problem. It’s quite obviously a bad solution – but it’s a solution nonetheless. Something that started out as a coping mechanism to numb or distract from pain in someone’s life gradually took control of them until they could no longer stop. Solomon says, “Every addict had a honeymoon, during which they could control their use.” In short, it was a coping mechanism, but eventually the coping mechanism took control.

Depression and substance use disorder (SUD) – which is the preferred terminology now – are related. When you’re depressed, you’ve got a part of your life you want to numb, and substances do that. When it’s become an addiction, you start to lose connections with others, financial resources, stability, and sometimes even dignity. That triggers depression. They feed each other until they’re stopped.

Another view is that substance abuse is the substitution of a “comfortable and comprehensible pain” – the consequences of the addiction – for an “uncomfortable and incomprehensible pain.” The uncomfortable and incomprehensible pain may not even be conscious. It may be something that we’ve never been equipped to find or deal with. If the substance takes away the pain from that, then it seems like its pains are a good bargain.

Time of Decide

One of the most effective interventions for suicide prevention is restriction to means. (See Rethinking Suicide for more.) People won’t often change their tool of choice from guns to drugs to bridges. When you prevent access, you often prevent death. We see it in suicide fences on bridges – which prevent people from jumping to their death. We see it when gun locks are introduced into a population. We see it wherever we work to block an avenue of death.

Seen differently, thoughts of suicide and the cognitive constriction that comes with it are often fleeting. One moment, suicide seems like the only option, and the next moment, you’re left wondering how you could have possibly thought that – that is, of course, if you didn’t have access to the means you needed to carry the thought out.

When we’re considering how to decrease suicide, delaying is our friend. Knowing that you don’t have to decide right this moment whether you want to die by suicide – you can defer that decision until later – may be helpful. It’s not ideal. We want people to cross it off the list of possible options – but for some people, that it is not possible or realistic.

Suicide and the Survivors of Concentration Camps

Victor Frankl wrote Man’s Search for Meaning as a way of chronicling the conditions of concentration camps but more importantly, to give hope that even in the worst of conditions humanity perseveres. The problem is that too many of those rescued from concentration camps would later come to die by suicide. The specific reasons aren’t clear.

Maybe they survived the camp only to have taken on too much mental anguish to continue forward on their own. Maybe their hopes that their loved ones were still alive were dashed when they were freed, and they no longer felt as if they had anything to live for.

Whatever the reason, those who walked or rode out of the camps didn’t seem to have the tools they needed to free themselves from the memory of the camps and the tragedies they were forced to live among.

Proactive vs. Reactive

One of the challenges with depression, like all of healthcare, is that we often look towards solving things once they’ve become problems. We don’t look for ways to prevent problems from occurring in the first place. The old saying is “A stitch in time saves nine.” Yet, we continue to battle depression and suicidal ideation after it’s formed rather than looking for ways to create mental health – rather than avoiding mental illness. If we can be proactive, we’ll spend less – but that takes time and isn’t always in the politicians’ best reelection interests.

Mental Illness, the Family Secret Everyone Has

The thing is that every family has mental illness somewhere. We ignore it, avoid it, and dare not discuss it, because it’s somehow shameful. It’s sort of like passing gas – everyone does it, but no one wants to admit it. The net effect is that we push mental health into the shadows and only want to address it when we see the next mass shooting. We address mental health when it becomes visible, and someone demands that we put an end to the tragedies that those with untreated mental illnesses inflict on others – but by then, it’s too late.

Sleep

One of the most overlooked and undervalued aspects of our human existence is the need for good, quality sleep. It’s the brain’s way of rejuvenating, cleaning, and processing the day, yet we’re chronically sleep deprived. We’re constantly trying to shave off a few minutes of sleep to get one more thing done – but in the process we’re making ourselves more depressed, more likely to attempt suicide, and generally miserable. Prioritizing sleep is one thing that we can all do to reduce depression – and too few of us can make this a priority.

The opposite of depression is life. Maybe you can find your way by studying the maps in The Noonday Demon.